The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #45 - #A45

#45 Combination plane 10 1/2"L (11 1/2" 1897 on), various widths (see below), 9 1/2lbs, 1884-1962.

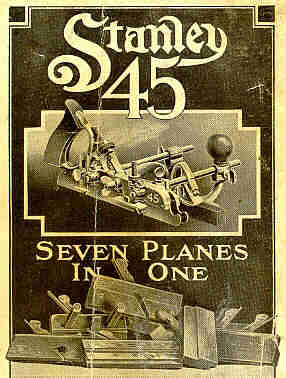

This

is Stanley's most famous and popular combination plane. A combination plane is

one that can be fitted with different irons, or cutters, as Stanley called

them, and be adjusted for a particular cut. The basic #45 can groove,

rabbet, dado, match (tongue and groove), bead (edge and center), slit, and cut

sash. With the special bottoms and cutters, which were purchased separately

from the basic model, the plane can do simple moldings, nosing, reeding, and

fluting. The images that follow (in order) show a catalog cover, a Type 1

model, a close-up of the Type 1's fence, a Type 5 in its original rare green

box, the commonly missing parts, the two style of cam rests, and an earlier

wooden carrier for all the cutters.

This

is Stanley's most famous and popular combination plane. A combination plane is

one that can be fitted with different irons, or cutters, as Stanley called

them, and be adjusted for a particular cut. The basic #45 can groove,

rabbet, dado, match (tongue and groove), bead (edge and center), slit, and cut

sash. With the special bottoms and cutters, which were purchased separately

from the basic model, the plane can do simple moldings, nosing, reeding, and

fluting. The images that follow (in order) show a catalog cover, a Type 1

model, a close-up of the Type 1's fence, a Type 5 in its original rare green

box, the commonly missing parts, the two style of cam rests, and an earlier

wooden carrier for all the cutters.

It was inevitable that planes of this design and function would be introduced for several reasons: the wooden plane business was on its last leg, technological advances in casting and design accelerated, and the reduced space and weight (in total) of them over the wooden planes they replaced.

Stanley didn't originate the idea of combination planes, but they were the one to popularize them and were the last one to be standing in the combination slugfest. Would be contenders, such as Siegley, Fales, and Walker were all left in Stanley's dust during the mad rush to build a better combination plane.

I hate them. There, I said it right off. Why? I find them to be tempermental beasts, where it seems just as much time is spent setting them up as there is when using them (obviously this isn't the case when sticking 10's or 100's of feet of stuff). Then there is their problem with tearout; stock selection is very important to use them satisfactorily. Unlike the wooden planes that the #45 replaces, there is no complete bearing surface ahead of the cutter. Instead, two narrow skates 'serve' that function. As a consequence, the majority of the iron has a mouth that is, in essence, infinitely wide, which, naturally, makes for suboptimal results. Now, the wooden planes (that the #45 replaces) aren't known for the tightness of their mouths, and as a result will tearout on grain changes. But, I've found the amount of tearout to be far less than that of a #45. Beads are the worst performer of the #45, and I'd rather use 'lectrical tools to make sash than to use this plane for the same.

One other thing I dislike about combination planes is that they are heavy, much more so than the wooden planes. Wooden planes, because they are dedicated to a particular task, only need to have their irons set and then it's off to the planing. Oh, I thought of something else bad about the #45 - there are too many parts that can get lost or broken, which any owner of a #45 is all too familiar.

My personal opinion aside, these planes are useful for many people. Those folks who do not have the space for, nor the chance to acquire, the wooden planes the #45 replaces find them very useful. The #45 also is cheaper than having to buy all the other planes it replaces. If I had to use the plane (like if a gun was stuck to my head, or something like that), I'd only do so for making reeds. It does a respectable job of that, provided the wood's grain is even, and you have copious scraps of wood about to test the plane's setting with each adjustment. It also ploughs about as well as any wooden plane, but that's because wooden ploughs, like the #45, do not have a complete bearing surface ahead of the cutter.

What follows is a list of all the parts found on a complete #45. Some of the parts were introduced later during the plane's lifetime. Like everything Stanley produced, the parts were numbered for ordering and inventory control. None of the numbers that follow appear on the parts.

- #1 Set of cutters (explained later).

- #16 Main stock - the part with the rosewood tote and a fixed skate.

- #23 Cutter bolt - wingnut-activated bolt to secure the cutter.

- #24 Cutter bolt wignut - fixed to the cutter bolt.

- #25 Cutter bolt clip and screw - secured to right side of the main stock to prevent the bolt from working free.

- #27 Cutter bolt adjustment screw - the screw that engages the cutter with a pin on the bottom of it.

- #28 Cutter bolt adjustment wheel - the wheel held captive in the main stock through which the adjustment screw passes; both #27 and #28 are used to set the cutter's depth.

- #29 Arm set screws - the pair of screws that fix the arms to the main stock.

- #30 Sliding section - the leftmost skate that is set to the cutter's width; it rides on two arms.

- #50 Left fence - the adjustable fence that regulates how far onto the wood the plane makes its cuts; it is secured to the arms with screws and has a rosewood strip screwed to it.

- #60 Long arms - a pair of round arms onto which parts are fixed to control the plane's cut; they're around 8 1/4".

- #61 Short arms - like #60, only shorter; around 4 1/2" long.

- #70 Adjustable depth gauge - an L-shaped threaded gauge that is fixed to the main stock.

- #71 Adjustable depth gauge nut - the knurled nut that regulates the setting of #70.

- #73 Adjustable beading stop - the L-shaped gauge that fits into the sliding section; a screw like #29 secures it.

- #75 Slitting cutter stop - a stamped metal stop to control the slitting cutter's depth; it is located near the tote.

- #76 Thumb screw - along with a washer, is used to hold the slitting cutter and its stop.

- #80 Cam rest - a D-shaped stop that is fixed to the arms to give additional support when planing; this was added ca. 1905.

- #81 Cam rest set screw - the screw used to secure the cam rest.

- #85 Spurs with screws - the spurs that are fixed to the skates, forward of the cutter; there are two - one on each skate.

Click here for an exploded catalog drawing of the plane (ca. 1935).

There is a rosewood knob

that is either attached to the main stock (on the earlier models) with a

threaded post and a cylindrical slotted screw or is attached to the fence's

main casting (on the later models). This knob, located toward the front of the

plane, is provided so that sufficient lateral pressure can be applied to the

plane, keeping it bearing against the edge of the stock being worked. The

earlier knobs are prone to splitting about their base and are rather fragile.

Stanley later moved the knob to the left fence. In this configuration the knob

screws directly to a threaded boss on the fence's casting. Sometimes, the knob

strips and won't stay fastened to the fence. Check for this damage by

unscrewing the knob from the casting.

There is a rosewood knob

that is either attached to the main stock (on the earlier models) with a

threaded post and a cylindrical slotted screw or is attached to the fence's

main casting (on the later models). This knob, located toward the front of the

plane, is provided so that sufficient lateral pressure can be applied to the

plane, keeping it bearing against the edge of the stock being worked. The

earlier knobs are prone to splitting about their base and are rather fragile.

Stanley later moved the knob to the left fence. In this configuration the knob

screws directly to a threaded boss on the fence's casting. Sometimes, the knob

strips and won't stay fastened to the fence. Check for this damage by

unscrewing the knob from the casting.

Surprisingly, many of the fences for these planes can be found damaged and/or repaired. Often, the slender portion of the fence's casting, where it curves downward from the arms, cracks. These cracks render the plane useless, and many guys had the cracks welded. Look all around the fence for any signs of repair. On those models that have a rosewood face to the fence you can find the rosewood all banged up or split. This is easy to fix with another piece of wood, but finding Brazilian rosewood, what Stanley used on them, might prove difficult. And while on the subject of the fence, the fence can be turned 180 degrees (end-to-end) so that the rosewood is on the outside and the knob is over the rear arm. This feature allows you to work farther into the wood by another 2", which can be handy when doing center beads, because the fence's arms are curved.

On the main stock check

that the cutter adjustment mechanism (those later models that have them) works

easily and that the area of casting that holds it isn't cracked. The cutter

bolt can sometimes not pop free when the cutter bolt is backed off. If this

happens, disassemble the entire cutter securing parts and clean them. On the

models that have the cutter bolt clip, check that neither of the

"tines" is gone. Check that the spur is still present on the right

side of the skate, and while you're at it check the sliding section's left side

of the skate for its spur. Both these spurs mount flush to the surface of their

respective skates with a countersunk screw.

On the main stock check

that the cutter adjustment mechanism (those later models that have them) works

easily and that the area of casting that holds it isn't cracked. The cutter

bolt can sometimes not pop free when the cutter bolt is backed off. If this

happens, disassemble the entire cutter securing parts and clean them. On the

models that have the cutter bolt clip, check that neither of the

"tines" is gone. Check that the spur is still present on the right

side of the skate, and while you're at it check the sliding section's left side

of the skate for its spur. Both these spurs mount flush to the surface of their

respective skates with a countersunk screw.

The beading gauge, the long depth stop-like piece with a 'rabbet' milled in it, is used to bead matched boards. Matched boards are nothing but boards that mate with each using a tongue and groove joint, and were all the rage during the late 1800's to the first quarter of the 20th century. The boards are oriented vertically and more often than not decorated with a bead on the tongue side of the board. To make matched boards, you cut the grooves and tongues on all the stock using the appropriate cutters for those tasks. The beading gauge is then fit into the forward hole of the sliding section, with the beading gauge's rabbet fitting snugly against the sliding section's skate. The sliding section is then positioned as it normally is for side beading, with the beading stop now functioning as the fence, riding above the tongue. The regular fence is not used for this operation. Beading gauges on the earliest models are japanned, and were later nickel plated when the rest of the plane received the same treatment.

The plane underwent

several modifications to its design during its long period of production. The

most noticeable difference between the early and late models is the plane's

finish. The earliest are japanned, while the later are nickel plated. It would

take several pages to describe all the changes made to the plane over its long

period of production. However, a few major changes are noted to help you date

your plane or to point out any incompatibilities amongst the models.

The plane underwent

several modifications to its design during its long period of production. The

most noticeable difference between the early and late models is the plane's

finish. The earliest are japanned, while the later are nickel plated. It would

take several pages to describe all the changes made to the plane over its long

period of production. However, a few major changes are noted to help you date

your plane or to point out any incompatibilities amongst the models.

The oldest models have their arms threaded into the main stock, whereas those produced after ca. 1900 slide through the main stock. The castings of the main stock and the fence are embossed with floral motifs and are japanned. Starting ca. 1890, the castings, while still cast with floral (on the main stock) motifs, are nickel plated. Starting ca. 1895, the cutter adjustment screw was added just forward of the handle casting, a strip of rosewood was added to the inside edge of the iron fence, and the rosewood knob was moved from the main stock to the fence. Starting ca. 1910, all floral motifs were removed from the castings and replaced with a stippled pattern. From here on, the plane remained pretty much unchanged, except for variations in the trademarks and some subtle casting changes.

The screws used to

secure the parts in position also offer a clue about the plane's date. The

earliest are unslotted brass screws. For a few years afterward, the planes came

equipped with slotted brass screws. Starting around 1890, the slotted screws

were nickel plated and remained that way until ca. 1900 when the screws were

replaced with flattened thumbscrews.

The screws used to

secure the parts in position also offer a clue about the plane's date. The

earliest are unslotted brass screws. For a few years afterward, the planes came

equipped with slotted brass screws. Starting around 1890, the slotted screws

were nickel plated and remained that way until ca. 1900 when the screws were

replaced with flattened thumbscrews.

For grooving, the sliding section is normally not used with the narrower cutters - cutters around 1/4" and less can be used without the sliding section since they don't suffer flexing along their left edge like the wider cutters do. When cutting wide grooves or wide rabbets, the sliding section is mandatory as it lends support to the wider cutters. If you note that the wider cutters are giving you fits, and the sliding section is situated to the leftmost edge of the cutter, you might want to move the sliding section closer to the main stock a bit as this tends to stabilize the cutter by preventing flexing about the middle of the cutter.

The sliding section and the fence tend to bind as they are moved about on the arms. The jumpy movement of them during setup often makes for a tough time of getting the accuracy you desire. This can be a real pain in the arse, and Stanley took steps to address it. Starting around 1915, a fine adjusting screw was provided for in the fence. A single knurled thumb screw can tweak the rosewood strip to set how far from the board's edge the plane works, which is a real benefit when trying to cut a groove, a bead, or whatever at a precise location. Because of this feature, planes made during this era and later are more in demand (by users) than the earlier models are. One thing to check on planes with this kind of fence is the presence of a locking thumb screw tapped into the lower front part of the casting. This thumb screw locks the rosewood strip in the position you set. Many planes are missing this thumb screw.

Many folks have no idea what the slitting cutter is used for, nor are they appreciative of what a clever and powerful little gizmo this thing is. It, along with its pressed steel depth gauge, are usually MIA, but replacements are fairly easy to find. Once you use the slitting cutter, you'll realize just how cool it is, and your fingers will forever stay attached to your hands since you won't have to resort to that dangerous spinning blade that sticks up from a cast iron table to rip thin strips of wood. The slitting cutter and depth stop are attached to the plane in a milled area located at the right rear of the plane, just forward of the handle (earlier models attach the slitting cutter over the extra long rear arm). The fence is used to position how far into the wood the slitting cutter does its slitting thing, and the depth stop controls how deeply into the wood the slitter goes. With the slitting cutter extended below the stop, all it takes is a few passes to cut a thin strip off a larger piece of wood (if the wood is thick, you usually run the slitter from both faces). This function is very useful for slicing beads from the wood so that you can use them to decorate whatever your mind can imagine.

The cam rest, first added

during the very early 1900's, is a clever and useful device, but only when you

need it, which isn't very often. If you want to cut a bead, or anything else

for that matter, way in the middle of a wide board, the distance between the

fence and the main stock is rather great. In this configuration, the plane is

apt to rock laterally making it somewhat difficult to use. The cam rest solves

this problem by providing an intermediate bearing surface between the fence and

the main stock. The cam rest is positioned between the two parts, roughly

equidistant from each. There is one slight gotcha with the cam rest - it

prevents the plane from cutting deeper into the wood on successive passes since

it behaves just like a depth stop. You solve this problem by pivotting the cam

rest back toward you just a hair and then taking the next pass with the plane;

the cam rest is an eccentric shape making it possible to adjust its depth

finely. If you set the cam rest's thumb screw so that it's tight enough to

resist movement during use, but not tight enough that you can force it to move

with your brute strength, you can avoid the hassle of loosening, positioning,

and tightening it between successive passes.

The cam rest, first added

during the very early 1900's, is a clever and useful device, but only when you

need it, which isn't very often. If you want to cut a bead, or anything else

for that matter, way in the middle of a wide board, the distance between the

fence and the main stock is rather great. In this configuration, the plane is

apt to rock laterally making it somewhat difficult to use. The cam rest solves

this problem by providing an intermediate bearing surface between the fence and

the main stock. The cam rest is positioned between the two parts, roughly

equidistant from each. There is one slight gotcha with the cam rest - it

prevents the plane from cutting deeper into the wood on successive passes since

it behaves just like a depth stop. You solve this problem by pivotting the cam

rest back toward you just a hair and then taking the next pass with the plane;

the cam rest is an eccentric shape making it possible to adjust its depth

finely. If you set the cam rest's thumb screw so that it's tight enough to

resist movement during use, but not tight enough that you can force it to move

with your brute strength, you can avoid the hassle of loosening, positioning,

and tightening it between successive passes.

There are two styles of cam rests. The first style has a thumb screw that sticks up from it. This style has a slit cut into the cam rest's casting so that the casting pinches the rod as the thumb screw is tightened. This style proved too costly to manufacture and was quickly redesigned to the form most commonly found with the plane. This new style has a set screw that's oriented horizontally into a solid (no slit) casting. The set screw pushes a rod that's inserted into the cam stop. This rod then exerts pressure onto the arm and locks the cam rest in place. A lot of these later cam rests are missing their internal rod. If it's missing, it's an easy thing to replace

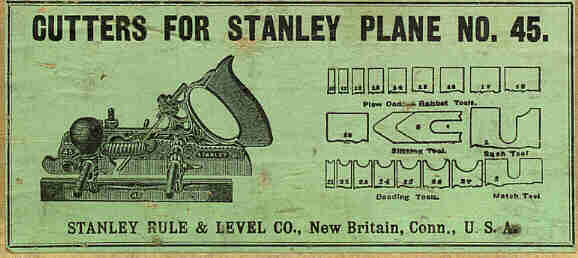

Now for all those blasted cutters. Here again, some of the cutters were introduced later during the plane's lifetime. However, there is a core set of them that were offered with the plane during its entire production. The following tables show all the "standard" cutters that were offered with the plane, and the year that they were first offered (the year that they were first noted in literature).

Cutters First Offered in 1884

|

beading |

1/8", 3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2" |

|

ploughing |

1/8", 3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2", 5/8" |

|

slitting |

V-shaped |

|

tonguing |

1/4" |

Cutters First Offered in 1897

|

ploughing |

3/4" |

|

sash |

1 1/2" (made optional in 1914) |

Cutter First Offered in 1914

|

fillister |

1 1/4" |

Cutter First Offered in 1919

|

plough |

13/16" |

Click here for a catalog drawing of the standard cutters.

The cutters came in wooden boxes (the earlier models) or cardboard boxes (the later models). The cutters can be used in the #55, but the reverse is not true for some of the cutters of the #55. Some of the #55's complex profiles need an additional skate to work, which the #45 doesn't have.

Some other cautions about the cutters need mentioning. The earliest cutters do not have the cutout on them to engage the pin on the cutter bolt adjustment screw, so these older cutters cannot be used on those models of the #45 that have the adjustment screw, unless you want to make the cutouts yourself. The matching cutter, the one that cuts the tongue, has a small and adjustable stop that fits into the cutter. This stop regulates how long a tongue is cut with the tool since it's impractical to use the normal depth stop when cutting tongues; there isn't any place for the normal depth stop to make contact and stop the plane from cutting. Many of these matching cutters are missing their depth stops.

You might notice the

addition of the odd size of 13/16" for the ploughing (in 1919) and

matching (in 1925). This strange dimension also made its debut in 1919 for the #39 13/16. Why this particular dimension all of

a sudden appeared in the Stanley offerings is unknown to me. Some wooden plane

manufacturers offered wooden dado planes in the 13/16" width, back during

the last quarter of the 19th century. There must have been some trade that

required this dimension, or perhaps 13/16" became the standard thickness

for wood much like 3/4" is our standard today. However, if it was a

standard back then, there certainly isn't the expected number of planes sized

to work that dimension out there.

You might notice the

addition of the odd size of 13/16" for the ploughing (in 1919) and

matching (in 1925). This strange dimension also made its debut in 1919 for the #39 13/16. Why this particular dimension all of

a sudden appeared in the Stanley offerings is unknown to me. Some wooden plane

manufacturers offered wooden dado planes in the 13/16" width, back during

the last quarter of the 19th century. There must have been some trade that

required this dimension, or perhaps 13/16" became the standard thickness

for wood much like 3/4" is our standard today. However, if it was a

standard back then, there certainly isn't the expected number of planes sized

to work that dimension out there.

The plane can also be equipped with extra bottoms, that were originally purchased as options. These bottoms are used to cut hollows and rounds, or a nosing. The bottoms are dedicated to a particular size, and come equipped with a cutter of the appropriate size. Each bottom fits onto the arms, and mates with the skate of the main stock. The sliding section isn't used when the extra bottoms are. The earliest bottoms are japanned and have no number cast into them; they use slotted brass screws to secure them to the arms. The later ones have a matte nickeled finish for their surface and a number cast into them; they use nickeled slotted screws or thumb screws to fasten them to the arms. The nickel plated bottoms can be found with their respective part numbers embossed on them. The following table lists the extra bottoms and the years they were offered.

Extra Bottoms Offered from 1885 - 1942

|

#6H & #6R |

3/4" hollow & 3/4" round |

|

#8H & #8R |

1" hollow & 1" round |

|

#10H & #10R |

1 1/4" hollow & 1 1/4" round |

|

#12H & #12R |

1 1/2" hollow & 1 1/2" round |

Extra Bottom Offered from 1892 - 1942

|

#5N |

1 1/4" nosing |

Click here for a catalog drawing of the bottoms.

There were also other optional cutters that were offered. They do not need the auxiliary bottoms, like the hollows and rounds and the nosing tool. They are secured into the plane like any of the basic cutters are. A complete set of these cutters, in their original boxes, is more valuable than the complete plane is. The following table lists the optional cutters and when they were first offered.

Optional Cutters First Offered in 1889

|

reeding (ordered in 2, 3, 4, and 5 reeds) |

1/8", 3/16", 1/4" |

Optional Cutters First Offered in 1914

|

sash |

1 1/2" (rabbet on left side of cutter) |

|

matching |

3/16" |

|

beading |

5/8", 3/4" |

|

fluting |

3/16", 1/4", 5/16", 3/8", 7/16", 1/2", 5/8", 3/4" |

Click here for a catalog drawing of special cutters.

All of the cutters have a part number associated with them. This number is often stamped on the face of the cutter, up near the heel. The same numbering system that was used on the #55's cutters (which see, if you're at all interested in that minutia) was also used for the #45.

#A45 Combination plane 10 1/2"L, various widths (see above, I don't feel like typing the cutter junk again), ~5lbs, 1926-1934. *

This was another one of Stanley's boneheaded ideas as far as popularity is concerned. However, this is one plane where it makes some sense to have the plane as light as possible. The public didn't buy it, and the plane is very rare.

Every part of the plane that fastens onto the rods - the main stock, the sliding section, the fence, and, yes, the cam rest - are made of that perfect metal for tools, aluminum. The plane is fitted with a rosewood handle and a rosewood fence, just like those found on the cast iron model.

There are some examples of this plane that have iron cam rests, and I'm told that they are original to the plane. I've had the misfortune of owning only one of these aluminum monstrosities, and its cam rest was aluminum. You be the judge whether the cam rest should or shouldn't be aluminum, but keep in mind that there are reproduction aluminum cam rests out there.

If you're missing one of these parts, you can step to the rear of the "Need parts for my #45" line. Do allow plenty of space between you and the person in front of you to permit newcomers to cut in line, however, since Shelton planes will be a hot collectible by the time you locate a proper aluminum replacement part for your plane.

Most of the models have "A45" cast into them. There are a few that do not, and just have "45" only cast into them. The Stanley Operating Committee voted in 1915 the authorization to produce the #45 in aluminum and the quickest means to the end was to use the same patterns as those of the cast iron model, which don't have the "A" prefix for them. The plane was offered earlier than the 1926 year listed above, but that year is the earliest catalog reference. Stanley did have the habit of introducing new planes with little fanfare; i.e., dedicated pamphlets or advertising in magazines before the plane made it into their catalogs, possibly to spare them any embarassment should the plane prove to be a miserable flop. Nah, check that. Nothing stopped Stanley from making stupid planes, with the nightmares-come-true #193 "fibrebored" planes as proof of that.

Stanley used different boxes to pack the plane. Some of the boxes are just the regular hard cardboard #45 boxes with a small printed label that reads "ALUMINUM" pasted on the larger green label. Other boxes have labels that have "A45" printed on them.

Aluminum isn't a very forgiving material. Check the plane carefully for cracks, breaks, bends, dings, etc. Don't bother looking for rust or peeling nickel plating (on the larger castings) - you won't find either on this one.

[ START ] | [ PREV ] | [ NEXT ] | [ END ]

[ HOME ]

Copyright (c) 1998-2007 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved. No part may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the author.