The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #60 - #70

Quick Find: #60, #60 1/2, #61, #62, #63, #64, #65, #65 1/2, #66, #69, #70

#60 Block plane, 6"L, 1 1/2"W (1 3/8"W 1914 onward), 1 1/4lbs, 1898-1950

This is the first in a

series of low angle (12 degrees) block planes that have the blade adjustment

mechanism most of us know and love. It consists of a knob fixed to a threaded

rod, which engages a sliding seat that's either cast iron or folded steel. This

sliding seat is machined (on cast iron ones) or stamped with protruding nibs

(on the folded steel ones) to engage a series of parallel machined grooves in

the backside of the iron. Thus, a turn of the adjustment knob either pushes forward

or pulls backward the iron to regulate the plane's set. I've seen a few

examples of this plane, and other similar model low angle block planes with the

same adjustment mechanism, that have had their adjusting knob snapped off the

threaded rod, only to be welded back together. This problem can be found on the

earlier model of the plane with the cast iron knob that has a coarse

"knurling" cast around its edge (these knobs are threaded onto the

adjusting screw and either have 6 holes drilled through them or

"STANLEY" cast into them. Check the joint of the knob and the

threaded rod for cracks or any repairs.

This is the first in a

series of low angle (12 degrees) block planes that have the blade adjustment

mechanism most of us know and love. It consists of a knob fixed to a threaded

rod, which engages a sliding seat that's either cast iron or folded steel. This

sliding seat is machined (on cast iron ones) or stamped with protruding nibs

(on the folded steel ones) to engage a series of parallel machined grooves in

the backside of the iron. Thus, a turn of the adjustment knob either pushes forward

or pulls backward the iron to regulate the plane's set. I've seen a few

examples of this plane, and other similar model low angle block planes with the

same adjustment mechanism, that have had their adjusting knob snapped off the

threaded rod, only to be welded back together. This problem can be found on the

earlier model of the plane with the cast iron knob that has a coarse

"knurling" cast around its edge (these knobs are threaded onto the

adjusting screw and either have 6 holes drilled through them or

"STANLEY" cast into them. Check the joint of the knob and the

threaded rod for cracks or any repairs.

The adjustment mechanism can become stripped through repeated use, if the lever cap is too tight on the plane. The adjusters that show signs of stripping normally have the damaged threads hidden by the cast housing into which the adjuster is screwed so you should back the adjuster off a good bit to examine the threads. When setting the iron, it's a good idea to back a bit of the lever cap's pressure off by slackening the lever cap's cam prior to adjusting, and then snapping the cam back into place when finished with the adjusting.

These planes do not have the lateral adjustment lever like the earlier (in the numbering sequence) block planes do; there simply isn't the room below the cutter to provide this feature. They all (except the #62 and #64) have the Hand-y grip depressions milled into their sides for gripping purposes (those models manufactured during WWII sometimes don't have the Hand-y grip). Several have adjustable mouths via the same mechanism as that used for the #9 1/2 (see that plane for blow-by-blow descriptions of potentional mouth problems) family of planes. All of the narrower low angle block planes of series have a smaller eccentric mouth adjuster, which while it is interchangeable with the wider block planes, it doesn't permit the full range of mouth adjustment.

Many of the low angle block are finished with nickeled trim, and have polished sides, but others are just japanned and polished and thus have a different model number. This particular model has its lever cap, front knob, eccentric mouth adjuster, and cutter adjusting knob nickel plated.

Many of these low-angle block planes can suffer chipping around their mouths, especially behind the cutter on its bedding. The shallow pitch of the cutter makes for a bottom casting that is very thin as it forms the bed. If the plane has a deep set, and is used on tough wood, the cutter can flex enough to place stress on the bottom casting causing it either to crack or to chip directly behind the cutter. Stay away from examples that show this damage, especially cracks. A minor and small chip behind the cutter isn't fatal, but those that resemble a saw's teeth and/or those that show signs of peeling back like a sardine can should be avoided.

The earliest models of this plane have a turned rosewood knob, which screws onto a threaded boss that's integral to the bottom casting. The patent date and "No 60" are embossed in the bottom casting, directly below the cutter adjustment wheel. They also don't have the eccentric adjustable mouth mechanism, like that found on the other later models. The adjustable mouth made its debut on the plane ca. 1902. This first model is somewhat scarce and is more useful as a collectible than as a user. It really is amazing that Stanley didn't debut this plane with an adjustable mouth since they had been providing that feature on the 20 degree block planes, like the #9 1/2, for decades. That Stanley had to have collector-whiff wafting through their nose hairs is the only reason I can come up with for not providing an adjustable mouth on this plane from the get go.

#60 1/2 Block plane, 6"L, 1 1/2"W, 1 1/4lbs, 1902-1982.

The standard low angle

block plane most of us recognize. It is identical in every way to the #60, except in its finish; its trim is japanned. This was

the common block plane used by many of us high school punks, when cutting our

teeth on block planes. See the #9 1/2 junk for

fixing the oft-encountered stubborn sliding sole section that this plane

develops.

The standard low angle

block plane most of us recognize. It is identical in every way to the #60, except in its finish; its trim is japanned. This was

the common block plane used by many of us high school punks, when cutting our

teeth on block planes. See the #9 1/2 junk for

fixing the oft-encountered stubborn sliding sole section that this plane

develops.

This plane is very popular due to its size - it fits nearly completely in an average-sized hand - and its weight makes it ideal for general trimming. It's one of the few planes you'll ever see used in that made for TV woodworking series hosted by the pretendah in plaid. The plane is a must-have for woodworkers, and I woulda been lost without mine while fitting clapboards on my digs while perched 20' in the air.

The plane can be found in several colors of paint (as it originally left Stanley, not the colors commonly found on it from it serving double-duty as a paint drop-cloth). The black and blue japanned models are both fine workers as Stanley's block plane standards didn't suffer tool-death at the same time that the bench planes did; i.e., blue painted block planes are fine whereas the same color on the bench planes should make you scream, run, and seek cover. Definitely stay away from the maroon colored block planes; Stanley must have hired some Greenwich Village arteest to come up with this hideous color.

The plane is usually found in a cosmetic condition that only a mother could love. The most frequently found model is the one with the cross-hatched knurling on the cutter adjusting knob, which is also stamped "STANLEY MADE IN USA". These models date from the 1930's onward.

#61 Block plane, 6"L, 1 3/8"W, 1 1/4lbs, 1914-1935. *

This plane is like the #60 in every way, except it never had an adjustable mouth

and it always was supplied with a turned rosewood front knob. This model is the

low angle model of the #9 1/4. These planes are

somewhat scarce, since Stanley offered similar block planes at a cheaper price.

They aren't tremendously valuable, at least in the sense that a Miller's Patent

is, but they are generally priced beyond what a user would pay for one.

Afterall, who'd buy a low angle block plane without an adjustable mouth?

This plane is like the #60 in every way, except it never had an adjustable mouth

and it always was supplied with a turned rosewood front knob. This model is the

low angle model of the #9 1/4. These planes are

somewhat scarce, since Stanley offered similar block planes at a cheaper price.

They aren't tremendously valuable, at least in the sense that a Miller's Patent

is, but they are generally priced beyond what a user would pay for one.

Afterall, who'd buy a low angle block plane without an adjustable mouth?

The plane has a nickel plated lever cap and adjuster, and the model number is embossed at the heel, below the adjuster. If you need a knob for this plane, you can lift it from the low budget #110.

#62 Low Angle Block plane, 14"L, 2"W, 3 5/8lbs,

1905-1942. *

This is one of Stanley's better

planes they ever decided to manufacture. It is nothing but a jack plane with

the block plane mechanisms added to it, instead of the common bench plane

mechanisms. It has its cutter seated at 12 degrees, an adjustable mouth, and

the depth adjustment knob like that found on the other block planes in this

series. There are several things to check out on this plane, before purchasing

one. Since the cutter is seated so low, and the fact that this is a powerful

plane (pushed like an ordinary bench plane), the mouth often chips, especially

in the area behind the cutter. You can flip over ten of these plane, and eight

of them will be chipped, one will not be chipped but repaired, and the last

perfect. You also want to check the side walls of the plane, down where they

blend into the heel and toe - these two areas are prone to chipping.

This is one of Stanley's better

planes they ever decided to manufacture. It is nothing but a jack plane with

the block plane mechanisms added to it, instead of the common bench plane

mechanisms. It has its cutter seated at 12 degrees, an adjustable mouth, and

the depth adjustment knob like that found on the other block planes in this

series. There are several things to check out on this plane, before purchasing

one. Since the cutter is seated so low, and the fact that this is a powerful

plane (pushed like an ordinary bench plane), the mouth often chips, especially

in the area behind the cutter. You can flip over ten of these plane, and eight

of them will be chipped, one will not be chipped but repaired, and the last

perfect. You also want to check the side walls of the plane, down where they

blend into the heel and toe - these two areas are prone to chipping.

The front knob is turned from rosewood and is unique to this plane. The knob sits atop a nickeled cast iron disk that has two projecting nibs on its top to fit into the underside (endgrain) of the knob. The disk is threaded to the bolt that passes through the knob and into the sole. The bolt needs to be tightened securely to the disk, placing pressure on the knob, so that the knob doesn't spin as you twist it to adjust the sliding section. Many times the bottom of the knob is split out or has a circular groove cut into its bottom since it's not secured tightly to the disk. If the knob is split badly, you may have to turn another one in order to adjust the plane as intended. The bolt threads into a boss in the sliding section. Sometimes this boss chips out, and won't grip the bolt well, making the plane less valuable for use and/or collecting. You should back the knob out completely to examine the boss. The boss can also strip (or the bolt itself can do the same). Be sure that the knob seats firmly and turns freely when it's screwed tightly.

The plane has the common

eccentric lever to adjust the long sliding section of the sole. This adjuster

is unique to the plane. The rosewood tote is also unique to the plane as its

toe is shorter than that used on the smaller bench planes, like the #3, since the adjuster needs some room to work

through its range. The lever cap, activated by a knurled thumbscrew, is nickel

plated and has a keyhole-shaped cutout through which the lever cap screw fits.

The nickel plated adjuster has a knob that's larger in diameter than the

similar ones used on the smaller low angle block planes, like the #65; you can tell if this adjuster is proper to the plane

by looking at how far off the main casting it sits - it should be no more than

1/8" above the casting. The bolt head used to secure the rosewood tote to

the main casting is nickel plated. The contrast between the japanned interior,

the nickel plating, and the rosewood give the plane a stunning look when new.

The plane has the common

eccentric lever to adjust the long sliding section of the sole. This adjuster

is unique to the plane. The rosewood tote is also unique to the plane as its

toe is shorter than that used on the smaller bench planes, like the #3, since the adjuster needs some room to work

through its range. The lever cap, activated by a knurled thumbscrew, is nickel

plated and has a keyhole-shaped cutout through which the lever cap screw fits.

The nickel plated adjuster has a knob that's larger in diameter than the

similar ones used on the smaller low angle block planes, like the #65; you can tell if this adjuster is proper to the plane

by looking at how far off the main casting it sits - it should be no more than

1/8" above the casting. The bolt head used to secure the rosewood tote to

the main casting is nickel plated. The contrast between the japanned interior,

the nickel plating, and the rosewood give the plane a stunning look when new.

Today, a lot of handplane lovers are buying a modern copy of this plane to use as a smoothing plane. So there we have it, smoothing planes have now been stretched to 14" long, probably because longer is better they think. I'd sure hate to use a plane this long to smooth a stubborn 1" area of tearout. Must be because I don't get it, or something. Stanley mustn't have gotten it, either, as they advertised as being designed for heavy work across the grain. Doesn't sound like smoothing to me.

One of Stanley's competitor's, Sargent&Co., made a version of this plane. Visit No. 514 to read all about it.

#63 Block plane, 7"L, 1 5/8"W, 1 3/8lbs, 1911-1935. *

Like the #61 in every way, except for length and width.

Again, a low angle block plane sold without an adjustable mouth makes for low appeal, making the planes fairly scarce.

#64 Butcher's block plane, 12 1/2"L, 2"W, 4lbs, 1915-1923. *

Hey, let's debate whether the

finish on this plane is suitable for its use on butcher's blocks (you'd have to

tune into everyone's favorite usenet site, rec.norm, to understand the hidden

meaning here - in other words, this is an 'inside' joke)! Yes, this plane is

used to square up the ends of butcher's blocks, and judging from the many years

of its being offered, it was a smashing success. Er, hardly! The plane is very

rare, as well as being very stupid. One has to wonder whether the head that

designed this DOA tool was put on the butcher's block to the cries of "off

with 'is 'ead!".

Hey, let's debate whether the

finish on this plane is suitable for its use on butcher's blocks (you'd have to

tune into everyone's favorite usenet site, rec.norm, to understand the hidden

meaning here - in other words, this is an 'inside' joke)! Yes, this plane is

used to square up the ends of butcher's blocks, and judging from the many years

of its being offered, it was a smashing success. Er, hardly! The plane is very

rare, as well as being very stupid. One has to wonder whether the head that

designed this DOA tool was put on the butcher's block to the cries of "off

with 'is 'ead!".

The plane came with two cutters - one serrated for roughing the endgrain, and another regular cutter for finishing the surface - it's very rare to find examples that have both their original cutters. The plane's bottom casting is entirely japanned inside and out, but not on the sole, just like the scrub planes, #40 and #40 1/2 are. This was done probably to make the casting somewhat rust-resistant, which was necessary when planing wet wood (all those bodily fluids oozing out of the animal flesh, which then seep into the wood, what with wood being wood, ya know?).

The tote and knob are beech. One might think that the beech tote on this plane would be interchangeable with that from a common transitional plane, but one would be wrong. The tote on this plane is unique to this plane. The plane very much resembles the #62 with its similar cutter adjustment, but sans the adjustable mouth. Its lever cap is unique as it doesn't engage a lever cap screw to act as a fulcrum point. Instead, it slips under a round rod that spans the cheeks of the plane.

You really don't want one of these for your shop unless you plan on having your workbench serve double duty as a place for Bambi dismemberment. Take out Barney, if you get a chance, please.

#65 Block plane, 7"L, 1 3/4"W (1 5/8"W 1909 onward), 1 3/8lbs, 1898-1969.

Yow, give the people what

they want - buying a block plane from Stanley was like buying a new automobile

with options galore. This one has the knuckle joint lever cap, like the #18 and the #19, but it

differs in its blade adjustment mechanism. Unlike the #18

and #19, with their vertical post blade

adjusting mechanism, this one has the threaded rod mechanism like the #60.

Yow, give the people what

they want - buying a block plane from Stanley was like buying a new automobile

with options galore. This one has the knuckle joint lever cap, like the #18 and the #19, but it

differs in its blade adjustment mechanism. Unlike the #18

and #19, with their vertical post blade

adjusting mechanism, this one has the threaded rod mechanism like the #60.

As proof that Stanley had a tough time making up their mind about their block plane offerings, this plane originally didn't have the knuckle joint lever cap, which was introduced on this plane ca. 1917. Prior to this date, it had the familiar stippled lever cap like that found on the #9 1/2, et al (see that plane for general info about the sliding sole section, eccentric lever, etc.). The first models of this plane don't have an adjustable mouth, then starting around 1905 they do. Then the knuckle joint lever cap was offered on the plane until ca. 1960, when it was trashed for the time tested and well loved stippled lever cap that it originally had.

This block plane is one of the finest planes that Stanley ever made, in my opinion. It certainly proved to be a real crowd pleasure in the user market. Unfortunately, many of them suffer cracking along the extreme ends of the bed, or chipping along the leading edge of the bed, right behind the iron. Examine the extremes of the bed very carefully to note whether there is any damage - it's often hard to notice.

Like the other low-angle block planes, the bottom casting doesn't have a lot of material at the bed where it feathers down to the mouth. A rank set of iron and/or too much clamping pressure via the lever cap is the usual cause of the damage here. Take care when using these planes since they are fragile - only use a fine set on them and they'll last you a lifetime.

#65 1/2 Block plane, 7"L, 1 5/8"W, 1 3/8lbs, 1902-1950.

Identical to the #60 1/2, except that its iron is wider. Like that

plane, the trimmings on this one are nickel plated; a japanned lever cap on

this plane is not correct as it, the adjuster, and the brass front knob are

nickel plated, with the latter's nickel plating normally long worn away.

Identical to the #60 1/2, except that its iron is wider. Like that

plane, the trimmings on this one are nickel plated; a japanned lever cap on

this plane is not correct as it, the adjuster, and the brass front knob are

nickel plated, with the latter's nickel plating normally long worn away.

The later models will have the number stamped into the side of the plane. If you see this number and the plane has a knuckle joint lever cap, it's a hybrid of this model and the #65. The hybrid will still work, provided that the lever cap screw is secured into the main casting well as the #65 1/2's screw is shorter than that required to accept the #65's knuckle joint lever cap.

The earliest model will have patent dates all over it: on the eccentric cam lever; on the lever cap; and embossed on the bed, directly below the sliding plate for the cutter, with "PAT. 8-3-97" (for the Hand-y grip, not for anything of the plane proper). Later models will have the plane's model number stamped into the left side, below the Hand-y grip. The early models are nowhere near as numerous as the later models, and the plane isn't nearly as common as its popular brother, the #65.

#66 Hand beader, 10"L (11"L 1909 onward), various widths (see below), 1 3/8lbs, 1886-1941.

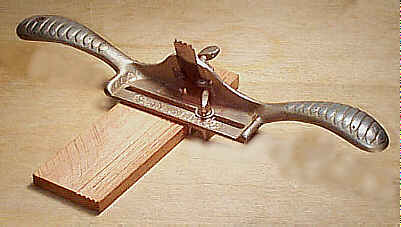

This is a spokeshave-like

tool used to bead, reed, or flute straight or curved surfaces. It has a thumb

screw mechanism used to secure flat cutters, which are identical to the kind

you'd make for a scratch stock. The thumb screw is threaded into a U-shaped

piece that's fastened permanently to the main casting; if the U-shaped piece is

broken or missing, you're S.O.L. as you can't readily pirate it from another

one as it involves heating metal so that it's pliable.

This is a spokeshave-like

tool used to bead, reed, or flute straight or curved surfaces. It has a thumb

screw mechanism used to secure flat cutters, which are identical to the kind

you'd make for a scratch stock. The thumb screw is threaded into a U-shaped

piece that's fastened permanently to the main casting; if the U-shaped piece is

broken or missing, you're S.O.L. as you can't readily pirate it from another

one as it involves heating metal so that it's pliable.

Two fences are supplied with the plane - one straight and one curved (see the image that follows). Each fence may be attached either to the left or the right of the cutter, but normally the fence is to the left of the cutter so that the tool can be pushed in the common right to left fashion. Additionally, the fences have a groove cast into them so that they can partially cover the cutter to permit them to cut only a portion of the cutter's profile. Usually, the fences are missing or only one remains, as well as the cutters being long lost. Examples that have everything with them are not as easy to find.

The earliest models are japanned, with the later ones, starting ca. 1900, nickel plated. The japanned models have the patent date incised in the concavity below one of the handles, and often have a tall and slender brass thumb screw to secure the fence to the stock. The nickel plated models have a textured surface to the handles and have a nickel plated common thumb screw to secure the fence to the stock. In both models, a washer is supplied with the thumb screw.

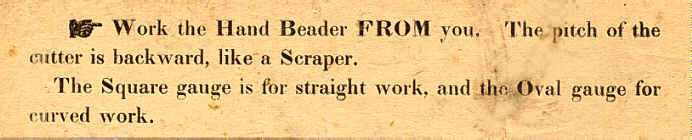

The tool functions

similarly to a scraper. The cutters are filed straight across, not beveled like

a plane iron is. The tool carries the cutter with a slight lean (off

perpendicular), and the tool is pushed or pulled with the cutter leaning toward

the direction of the tool's movement. It helps to increase the cutter's set

gradually on the cutters of the larger dimensions rather than having the entire

cutter exposed; if the cut is started with the entire cutter exposed, the tool

is apt to behave in a jumpy manner due to the sole not being in contact with

the wood.

The tool functions

similarly to a scraper. The cutters are filed straight across, not beveled like

a plane iron is. The tool carries the cutter with a slight lean (off

perpendicular), and the tool is pushed or pulled with the cutter leaning toward

the direction of the tool's movement. It helps to increase the cutter's set

gradually on the cutters of the larger dimensions rather than having the entire

cutter exposed; if the cut is started with the entire cutter exposed, the tool

is apt to behave in a jumpy manner due to the sole not being in contact with

the wood.

There are 8 cutters (earlier models only had 7, with the blank one optional on the earlier models), each ground on both ends making for a total of 15 sizes. The blank one could be ground to whatever shape was desired. The following cutters are supplied with the plane -

- 3 Single Beads: 1/8", 3/16"; 1/4", 5/16"; 3/8", 1/2".

- 1 Fluting: 3/16", 1/4".

- 1 2 and 3 Reeding: 3/16" (2 bead), 1/4" (3 bead).

- 1 3 and 4 Reeding: 1/8" (3 bead), 1/8" (4 bead).

- 1 Router: 1/8", 1/4".

- One blank cutter from 1909 on.

#69 Hand beader, 5"L, various widths (see below), 3/8lbs, 1898-1917. *

This is a lighter version beader

than the #66, and is made to be used with one hand.

It has a turned hardwood handle (maple or beech), and a nickel plated casting

to hold the cutter. The cutter leans forward in the casting, and protrudes from

the rear of it. A small, captive lever cap, activated by a smaller still

slotted screw, holds the cutter in place. Where the handle joins the casting is

a nickel plated ferrule, which often is found split. The ferrule splits from

pressure during use. The handle threads onto the main casting in the same

manner as the rosewood knob threads onto the #9 3/4, et al; the main casting

has an threaded integral projection at its rear.

This is a lighter version beader

than the #66, and is made to be used with one hand.

It has a turned hardwood handle (maple or beech), and a nickel plated casting

to hold the cutter. The cutter leans forward in the casting, and protrudes from

the rear of it. A small, captive lever cap, activated by a smaller still

slotted screw, holds the cutter in place. Where the handle joins the casting is

a nickel plated ferrule, which often is found split. The ferrule splits from

pressure during use. The handle threads onto the main casting in the same

manner as the rosewood knob threads onto the #9 3/4, et al; the main casting

has an threaded integral projection at its rear.

The first model of the tools has the patent date, "PAT. 2 9 86", cast into the lever cap. These models have a non-slotted lever cap screw. On the flat portions of the main casting, just ahead of the mouth, can be found "No. STANLEY 69" cast diagonally. It's interesting to note that this tool didn't make its appearance in a catalog until 1898, thirteen years after it was patented. However, the patent is actually for the #66, which was put into production soon after the patent was granted. The #69 simply was based upon the same patent, and thus was put into production later when the braincells were in overdrive at New Britain, where a single patent could be transformed into wads of similar but different tools.

The cutters are identical

to those provided with the #66, with the exception

of the router cutter, making for six in total. This beader has no fence, and is

designed to cut those beads/reeds/flutes that are difficult to cut with the

fenced #66. The tool normally requires the use of a

batten to guide it as it's pushed forward. Since these applications aren't all

that common, the beader didn't sell well, hence its rarity.

The cutters are identical

to those provided with the #66, with the exception

of the router cutter, making for six in total. This beader has no fence, and is

designed to cut those beads/reeds/flutes that are difficult to cut with the

fenced #66. The tool normally requires the use of a

batten to guide it as it's pushed forward. Since these applications aren't all

that common, the beader didn't sell well, hence its rarity.

As is the case with tools that have lots of parts, this tool is usually found with a single cutter, still clamped in place from the last time it was used. It's a very small tool that can easily be overlooked, so be certain to dig to the bottom of the box when out hunting tools in fleamarkets, auctions, yard sales, etc.

#70 Box scraper, 13"L, 2"W, 1lbs, 1877-1958.

This is a tool used to scrape the

markings from the wooden shipping boxes, which were the most common way of

packing goods prior to the invention of corrugated folding cardboard boxes,

styrofoam peanuts, bubble pack, and all sorts of modern wonderful shipping

products. The owner or user of this tool could scrape the previous shipper's

markings off and use the box over. It would be swell to think that Stanley was

being environmentally conscious here, but given their fetish for raping the

rosewood reserves, that notion of eco-fundamentalism is fantasy. The scraper

also can be used to scrape floors or other rough surfaces (you folks in the

northern climes, use it as a windshield scraper at your own risk).

This is a tool used to scrape the

markings from the wooden shipping boxes, which were the most common way of

packing goods prior to the invention of corrugated folding cardboard boxes,

styrofoam peanuts, bubble pack, and all sorts of modern wonderful shipping

products. The owner or user of this tool could scrape the previous shipper's

markings off and use the box over. It would be swell to think that Stanley was

being environmentally conscious here, but given their fetish for raping the

rosewood reserves, that notion of eco-fundamentalism is fantasy. The scraper

also can be used to scrape floors or other rough surfaces (you folks in the

northern climes, use it as a windshield scraper at your own risk).

It has a long, simply turned, maple (or similar hardwood) handle that has a lacquer finish on the earlier examples and a deep red paint on later examples. A japanned forked metal casting is fixed into the handle. At the end of the casting is a carrier for the cutter that can pivot 360 degrees to permit the tool to be pushed or pulled. A captive lever cap, activated by a simple thumb screw, holds the single cutter in place. The sole is slightly convex along the front and leading edges, and is also slightly convex over its width. The cutter is ground and honed with a shallow radius to the cutting edge, permiting the tool to work uneven surfaces; shipping boxes aren't perfectly flat (imagine that), and the convex cutting edge allows the tool to work these surfaces easier. The tool has a relatively wide mouth.

No one has yet written a definitive type study on these critters (don't understand why), but the logos stamped into cutters of these things pretty much follow the chronology of those on the common bench planes. Other than the noted change in the handle's finish, this tool remained unmodified from its birth to its death.

Box scraping is a rugged profession, and this tool doesn't often show signs of physical damage save for a check or two in the handle or a break in the brass ferrule (it's sometimes missing), but cosmetically it often looks like it was used to scrape barnacles off rocks. It certainly isn't a very elegant tool, but it is a useful one if you're into scraping boxes or whatever. I've never used it to scale a fish, but I don't see why it wouldn't tackle that job rather effectively. Be sure to rinse and pat dry after use.

[ START ] | [ PREV ] | [ NEXT ] | [ END ]

[ HOME ]

Copyright (c) 1998-2007 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved. No part may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the author.