The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #90 - #100

Quick Find: #90, #90 (bull nose), #90A, #90J, #92, #93, #94, #95, #96, #97, #98, #99, #100

#90 Steel cased rabbet plane, 9"L, 1 1/2"W, 2 5/8lbs, 1877-1888. *

This plane is identical

to the #80, described in an earlier posting, except that

this model has a spur

for scoring the grain before the cutter cuts the wood.

Like the #80 rabbet,

these planes are difficult to find without modification.

This plane is identical

to the #80, described in an earlier posting, except that

this model has a spur

for scoring the grain before the cutter cuts the wood.

Like the #80 rabbet,

these planes are difficult to find without modification.

The spur is dovetailed into the right side of the

steel casing. This same

means of attachment is commonly used on the wooden rabbet

planes contemporary

with this plane. The spur is removed for sharpening or

adjusted downward by

tapping it at its top. Often, the steel casing just above

the spur will be

munged as a result of jamming a screwdriver, or similar

tool, above the spur

and twisting it. On this model, the steel casing has an

extra screw on the spur

side so that the casing won't distort around the spur.

The image here shows how the original mouth should

look. Most examples have

their mouths filed with an arch-shape opening to allow freer

passage of the

shaving. See the #80 rabbet plane for a view

of what the mouth looks like

on the other side.

#90 Bull nose rabbet plane, 4"L, 1"W, 1lb, 1898-1969.

This is the first in a

series of so-called cabinetmaker's rabbet planes, and is the

rightmost one in

the image (the larger planes are pictured to show the

details of the text). They

were advertised as being "designed for fine Cabinet Work

where extreme

accuracy is required." The distinguishing feature of this

plane that sets

it apart from the others, other than its overall length, is

its very short toe

section. This section is roughly 1/4" long, which makes it

suitable for

bullnose work.

This is the first in a

series of so-called cabinetmaker's rabbet planes, and is the

rightmost one in

the image (the larger planes are pictured to show the

details of the text). They

were advertised as being "designed for fine Cabinet Work

where extreme

accuracy is required." The distinguishing feature of this

plane that sets

it apart from the others, other than its overall length, is

its very short toe

section. This section is roughly 1/4" long, which makes it

suitable for

bullnose work.

They all are cast iron, with full nickel plating. The

amount of original

nickel plating that remains on these planes has a tremendous

effect on their

value, but has absolutely no effect on their use. The sides

are ground flat

and, supposedly, square to the bottom. All the planes in the

series have the

"HAND-Y" grip feature, like that on the block planes, milled

into

their sides to allow for a more comfortable grip. They can

be used either right

or left handed.

Each plane's sole is of a two-section construction -

one section forms the

toe of the sole, and the other forms the heel of the sole.

The toe section sits

atop, and slides over, the heel section, and together they

are secured by means

of a large slotted screw. This screw is loosened to adjust

the plane's mouth by

sliding the toe section over the heel section, and then

tightening the screw.

Through repeated use, this screw can become mangled, so

check for that. Also,

check the area of the casting where this screw threads into

the heel section as

it's prone to cracking, which is impossible to see without

taking the plane

apart, and even with it apart a crack can be difficult to

detect. Check where

the screw butts against the toe section for any signs of

stress cracks that may

result from over tightening the screw.

The toe section can be

removed completely from the plane so that it can be used as

a chisel plane.

Stanley, in their tool propoganda, claimed that with the

plane configured as a

chisel plane it was useful for the removal of dried glue.

There are better ways

to remove that than to use this plane. However, the plane

does function nicely

as a chisel plane and is particularly useful when working

rabbeted frames,

where the stiles and rails join. The planes are a lot less

costly than the

dedicated chisel plane that the company made, the #97.

The toe section can be

removed completely from the plane so that it can be used as

a chisel plane.

Stanley, in their tool propoganda, claimed that with the

plane configured as a

chisel plane it was useful for the removal of dried glue.

There are better ways

to remove that than to use this plane. However, the plane

does function nicely

as a chisel plane and is particularly useful when working

rabbeted frames,

where the stiles and rails join. The planes are a lot less

costly than the

dedicated chisel plane that the company made, the #97.

Inside the toe section is a little set screw,

oriented parallel to the sole,

that can be set to regulate the mouth's opening. This set

screw is only

accessible when the plane is apart. It butts up against the

larger slotted

screw used to hold the two sections together. This little

set screw is what

keeps the mouth constant, to a pre-set width, as the two

sections are screwed together.

This capability to maintain the mouth's opening is a handy

feature to have,

though it is by no means mandatory, for the times that the

toe section is

removed, either to hone the iron or to use the tool as a

chisel plane.

The set screw oftentimes is seized into the toe

casting, which is something

you won't be able to tell unless you carry along a small

screwdriver to

disassemble the plane before you buy it. If the set screw is

seized, don't try

to free it without first letting it soak with some

penetrating oil - the slot

for the screwdriver may snap off, if you're impatient,

leaving you a fine mess

to solve. If you're having trouble closing the mouth of the

tool, you have to

drive the set screw deeper into the casting since it's

preventing the toe section

sliding farther back over the heel section as the set screw

is butting against

the larger slotted screw that secures the two sections

together. Some guys just

removed the set screw from the plane since they mustn't have

liked screwing

with so many screws.

The plane's cutter is

sorta spade-shaped (the shovel kind). It is pitched at

roughly 20 degrees, with

its two edges perpendicular to the cutting edge being

chamfered. The cutter is

as wide as the plane is over the length of the plane's bed,

where it abrubtly

diminishes to a constant width as it extends through the

plane's body, poking

out at the heel of the plane. The cutter is removed from the

plane through the

mouth whenever grinding or honing is required. The cutter is

used bevel-side

up, as is the case for most planes that have their cutters

pitched lower than

~35 degrees.

The plane's cutter is

sorta spade-shaped (the shovel kind). It is pitched at

roughly 20 degrees, with

its two edges perpendicular to the cutting edge being

chamfered. The cutter is

as wide as the plane is over the length of the plane's bed,

where it abrubtly

diminishes to a constant width as it extends through the

plane's body, poking

out at the heel of the plane. The cutter is removed from the

plane through the

mouth whenever grinding or honing is required. The cutter is

used bevel-side

up, as is the case for most planes that have their cutters

pitched lower than

~35 degrees.

A large, knurled adjusting screw protrudes from the

heel of the plane. This

screw activates a mechanism like that found on the #60's series of block planes;

i.e., the screw activates

a cast iron sliding section, which sits freely atop a

machined inclined plane.

Together, the sliding section and the inclined plane form

a sort of tongue and

groove so that the sliding section doesn't become

misaligned as it moves over

the inclined plane. The sliding section has a small nib on

it that engages

machined grooves in the cutter's backside.

The adjusting screw on the older models is larger and

somewhat cruder than

on the later models as it's a cast piece. The knurling is

coarser on the older

ones, and "STANLEY" is cast in a circle on the screw's knob.

On the

later models, it's sometimes difficult to tell whether the

plane is

American-made or English-made. The cutter, at its top, is

stamped with the plane's

origin. It's often hard to read the origin unless the plane

is taken apart. The

larger rabbet planes of this series have their country of

manufacture stamped

on the circular disk at the toe (see #92 for more about this disk) as

well as on their

cutter. The earliest models of the plane have the patent

date stamped into the

iron.

These planes, despite

Stanley's claim that they are machined accurately, are

sometimes not so. They

were offered as premium planes in direct competition with

the products made by

Norris, et al, in England. If you are hankering to own an

affordable

better-quality rabbet plane, these Stanley products are

certainly that, but

they are no match (surprise) to the English products.

Stanley made these planes

general purpose so that they can be used as regular rabbet

planes, chisel

planes, and shoulder planes. Their cutters are pitched lower

than might be

expected for rabbeting so that they can be used as shoulder

planes. The English

designed two distinct planes for these tasks, with each

particularly suited for

the tasks. However, the English versions, despite their

functional and visual

superiority over the Stanley versions, are considered very

expensive by most in

the user community, making the Stanley products an

affordable alternative.

These planes, despite

Stanley's claim that they are machined accurately, are

sometimes not so. They

were offered as premium planes in direct competition with

the products made by

Norris, et al, in England. If you are hankering to own an

affordable

better-quality rabbet plane, these Stanley products are

certainly that, but

they are no match (surprise) to the English products.

Stanley made these planes

general purpose so that they can be used as regular rabbet

planes, chisel

planes, and shoulder planes. Their cutters are pitched lower

than might be

expected for rabbeting so that they can be used as shoulder

planes. The English

designed two distinct planes for these tasks, with each

particularly suited for

the tasks. However, the English versions, despite their

functional and visual

superiority over the Stanley versions, are considered very

expensive by most in

the user community, making the Stanley products an

affordable alternative.

When buying these planes, it's good to carry along a

small machinist's

square to test them for truth. Also, check the mouth to make

sure that it

hasn't been tampered with (like filed) and that it is a

uniform width across

its length. Make sure that it isn't chipped, especially at

the corners, as they

sometimes are, or that it shows any signs of stress

cracking. Inspect the area

where the two sections mate, along its entire length, for

this is another area

that seems to suffer stress cracks or broken chunks off the

toe section. Sight

along the plane's sole to check that the toe section is

aligned with the heel

section. I've seen far too many examples of these planes

where they are not

aligned due to sloppy machining. This problem appears to be

found more often on

the later and larger (#92, #93,

#94)

examples of these planes.

By far, the most common damage that any of these

style planes can suffer is

found on their lever caps. The lever cap is secured in place

by turning a small

slotted cap screw, with a screwdriver, which causes the

lever cap to place

pressure on a bridge that spans the inside width of the heel

section. Since the

lever caps are rather long in relation to their thickness,

it's very easy for

them to snap in two. This damage is usually unseen, unless

the plane is

completely taken apart. Often, the break is welded and

ground flat. The repair,

if done well, has no effect on the plane's use, but a

collector will head for

the hills should one be waved under his nose.

All the above applies to each of these rabbet planes,

up to the #94 inclusive.

This model of the plane was the most popular in the

series, as judged by its

long production, and was the first in the series to be

offered by Stanley. It

seems as though Stanley was testing the waters before they

took the plunge to

make the longer planes. The first model of this plane

doesn't have its number

embossed anywhere on it, but eventually the number was

embossed at the top,

toward the toe. A copy of the plane, and its two larger

brothers, is still made

in England.

#90A Cabinet makers' rabbet plane, 4"L, 1"W, 1lb, 1937-1943. *

Just when I go and say all the above applies to

everything that follows,

Stanley decides to offer this little oddball. It's basically

the same plane as

the #90,

except that it's different (hohoho!). Hell, one might

assume that this one is

aluminum, if one followed Stanley's numbering scheme. But

no, this one ain't

aluminum. It appears that Stanley had enough sense to

never introduce that

metal to this style of plane.

What sets this plane apart from the #90 is that its body is a

one-piece construction. It is

a bullnose rabbet plane, but there is no provision to

adjust its mouth (like

the two section #90). It has a similar, but

different, blade adjusting

mechanism - a knurled nut engages a single slot in the

cutter, which is a

cheaper mechanism than that provided on the #90. The knurled nut travels over

a 1 3/8" long

threaded rod, which itself is threaded into the main

casting, at the heel of

the plane. The nut is stamped "No. 90A". The cutter has

"90A" stamped into it, but more importantly, it has "MADE

IN

USA" also stamped into it, which is very important, if

you're a collector

willing to shell out the $1000+ it takes to own this guy.

The lever cap isn't captive to the plane; you can remove it

completely from the

plane, which must be done to remove the iron. The lever cap

has a small locking

wheel beneath the area where you rest your palm. This wheel,

when turned,

places pressure directly below on the iron, and forces the

lever cap upward

against the main casting (this style of lever cap is common

on the English-made

rabbet and shoulder planes). The lever cap has "STANLEY"

embossed in

the palm area, and "MADE IN USA" down where it rests above

the honed

edge of the cutter. Again, "MADE IN USA" is mandatory for

this to be

a proper and complete USofA product. Check that the lever

cap hasn't been

brazed, cracked, or chipped. Be sure to look where the

locking wheel threads

into the lever cap's casting for any signs of damage.

Lastly, check that the

lever cap's little 'peak', where it engages the main

casting, isn't chipped or

broken.

These planes were never popular over here, and the

war helped to speed its

death. As a result, they are very rare. Afterall, why would

someone purchase a

non-adjustable rabbet plane, when the#90 offered the same

function, but with more bells and

whistles? Certainly not too many would, which accounts for

its scarcity. Even

the glitzy nickel plating of the thing couldn't boost

sales.

#90J Cabinet makers' rabbet plane, 4"L, 1"W, 1lb, 1937-1943. *

This plane is identical to the #90A, except with two differences. There is no blade adjusting mechanism other than the dexterity of your hands. The plane's top is japanned, with its sides polished. The Stanley English version of this plane is identical to this one, but it doesn't have the Made in USA logo on it. This, and the #90A are tough monkeys to find, but only of the USofA manufacture.

#91

No #91. Why Stanley didn't assign the #90A to this number we'll never know. Heck, they probably didn't know either. Heh, heh, heh, those guys in charge of number designation at Stanley sure were a riot!

#92 Cabinet makers' rabbet plane, 5 1/2"L, 3/4"W (1"W, 1962 on), 1 1/2lbs, 1902-1969.

Goto #90, read that, and

apply these dimensions to get a feel what this plane is.

Goto #90, read that, and

apply these dimensions to get a feel what this plane is.

But wait, there's a bit more to be said about this

plane, the #93, and the #94, which cannot be

said of the #90. These longer planes have toe sections that are

much longer than the

small bull nose toe section of the #90. Consequently, there was a

tendency for these toe

sections to become misaligned with the heel section over

time due to the

internal stresses inherant to cast iron.

The earlier models of these larger planes have solid

toe sections. The later

models, ca. WWI onward, each have a circular disk that's

recessed and affixed

to the toe section. You don't want to go popping this disk

off to find out

what's behind it, but if you did, you'd find a hollowed out

toe section, filled

with a metal cylinder to give the plane its weight. By

hollowing out the toe

section, Stanley was able to overcome the risk of the toe

section warping in

relation to the heel section. This treatment was no

guarantee that the two sections

were aligned; sloppy machining would defeat that purpose.

The disk has the

company logo on it, and that logo reflects the one in vogue

during the time the

plane was manufactured.

The circular disk was dropped from the later examples

of these planes, and

the current English models don't have the disk. It's

probable that the cost of

manufacturing these planes with the disk became too

expensive so the planes

were made like they were when first offered - a solid toe

section, with no

disk.

The very first models of this plane, and its two

larger brothers that

follow, do not have the number cast into them. They also

have a composite toe

section where a portion of the front sole is cast separately

and then pinned to

the rest of the casting. This method of manufacture must

have been very costly

to produce, never mind the requirement of extreme accuracy.

Stanley probably

did this to help eliminate any movement of the toe section

long after that

casting was machined. The amount of mass of a solid toe

section could warp or

distort just a fraction, throwing the machined accuracy of

the toe section

relative to the heel section out of truth.

The mating edges of the toe section to the heel

section is also different on

the earliest model of these larger planes. They are machined

to form a broad

arch and thus only make contact with the heel section on 4

small edges, 2 on

each side. This method of mating the two castings was easier

to machine as

there was less area on the toe section that had to be true,

however the resulting

strength of this method didn't prove strong enough to hold

up during use, and

the method was dropped soon after it was tried.

Some of the planes can be found without the

strengthening cross rib that

spans the opening where the palm rests on the tool. The

model number, cast into

the flat length of the toe section, can be found oriented

relative to the heel

or the toe of the plane (the numbers are upside down to each

other when

comparing different models of the planes).

#93 Cabinet makers' rabbet plane, 6 1/2"L, 1"W, 1 3/4lbs, 1902-1964.

Goto #92, read that, and apply these dimensions to get a feel what this plane is.

#94 Cabinet makers' rabbet plane, 7 1/2"L, 1 1/4"W, 2lbs, 1902-1943. *

Goto

#93, read that, and

apply these dimensions to get a feel what this plane is.

This is the one plane

of the series that approximates the role of the heavier

and larger English

infill shoulder planes, and is a good alternative to those

expensive planes,

when this plane is found in its typical used condition.

Given this, it's no surprise that many of these planes are

found over in England, American buyers never fancied this

model.

This plane is the most difficult to find of the

series, and it's doubly

difficult to find in crispy, nickely new condition.

Furthermore, because of the

extra length of mating surfaces between the toe section and

heel section, the

machined area where the two meet can often be found cracked

or with chunks of

the toe section broken out. The planes also seem to suffer

cracks where the toe

section arches down to meet the heel section more often than

its smaller brothers

do. Check this area very carefully as cracks in this area

can be very difficult

to detect.

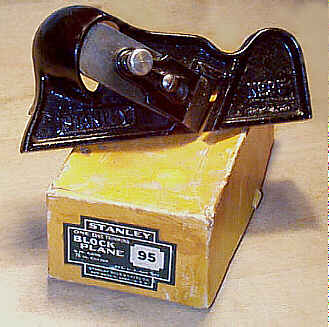

#95 Edge trimming block plane, 6"L, 1 1/16"W, 1 1/4lbs, 1911-1961.

This is another very

useful plane, which a well-equipped shop should have. It's

not an inexpensive

plane, but it's worth every cent you pay for it. Several

modern manufacturers

have made copies of this plane out of a glistening bronze

alloy, which can

oxidize and leave marks on your work just like the

forgetable aluminum bench

planes that Stanley dumped on happy planers of yesteryear.

One maker of these

planes supplies them in left and right hand versions. The

original only comes

in a right hand version.

This is another very

useful plane, which a well-equipped shop should have. It's

not an inexpensive

plane, but it's worth every cent you pay for it. Several

modern manufacturers

have made copies of this plane out of a glistening bronze

alloy, which can

oxidize and leave marks on your work just like the

forgetable aluminum bench

planes that Stanley dumped on happy planers of yesteryear.

One maker of these

planes supplies them in left and right hand versions. The

original only comes

in a right hand version.

The plane has a V-shaped sole that forms a right

angle. One leg of the V

carries the cutter, which is set at a skew, and the other

leg acts as a fence.

A small lever engages grooves machined in the back of the

cutter so that it can

be set by lifting or lowering the lever. Check that this

mechanism works well

and that the lever engages the cutter securely.

A screw-activated lever cap holds the cutter in

place. Sometimes, the screw

was cut a bit short, making it difficult or impossible for

the lever cap to

hold the iron in place securely. If the lever cap screw

'bottoms out' and the

iron's adjustment lever can be moved easily, the cutter will

not stay in place

during use. You can sometimes remedy the problem by

tightening the slotted

screw which the the lever cap engages.

Since the plane's sole is machined so that it forms a

right angle, the plane

is used to true up edges. It works equally well against the

grain or along the

grain. With a very fine set to the cutter, and a very keen

edge on the cutter,

the plane does very well on end-grain. A lot of guys like to

use this plane to

square up the edge after they've jointed it. While you can

do that, it's better

to learn to joint properly, and save this short soled plane

for other tasks.

The portion of the sole that's perpendicular to the

iron has two holes - one

at the toe and one at the heel - drilled in it so that you

can secure a

bevelled piece of wood on the sole to make it cut off of 90

degrees. This is

useful for bevelling edges. Just be sure to orient the wood

piece so that the

narrowest portion is toward the iron otherwise you can't

make effective use of

the relatively narrow width of the cutter.

The earliest model of the plane has the Stanley logo

in script to the lower

left of the cutter. On the back of the main casting can be

found the patent

date, "U.S.PAT.5.14.12", embossed above the sole.

Check that there are no chips or cracks on the main

casting and that the

lever cap hasn't been snapped in two and repaired. I've seen

a few of these

planes that have a hairline crack in the arched portion of

the casting just

behind the cutter.

In the wasteland of stupid planes Stanley ever

produced, this is surely one

that can't be categorized that way.

#96 Chisel gauge, 2 1/4"L, 3/8"W, 1/12lbs (yup, one over twelve pounds), 1888-1922. *

This is not a plane per

se, but it does function like one. What it is is a tiny

little gauge, which

sorta looks like a plane, that is fixed to a chisel to allow

blind nailing.

Blind nailing is where a shaving is partially lifted from

the wood's surface, a

nail is driven under the shaving's position, and the shaving

finally glued back

in place. The maximum width chisel the tool can accept is

1/4".

This is not a plane per

se, but it does function like one. What it is is a tiny

little gauge, which

sorta looks like a plane, that is fixed to a chisel to allow

blind nailing.

Blind nailing is where a shaving is partially lifted from

the wood's surface, a

nail is driven under the shaving's position, and the shaving

finally glued back

in place. The maximum width chisel the tool can accept is

1/4".

A captive lever cap, made of nickel plated cast iron,

fastens the gauge to

the chisel; a slotted screw actives the lever cap. The tool

is made of nickel

plated steel. Check that the sole is flat, and that it

hasn't been ground

convex as it's possible to find some examples that have been

so modified.

It's kind of a stupid tool, since a chisel alone, in

a skilled hand, can

accomplish the same thing. They are scarce little tools,

easily overlooked when

scrounging for old stuff. And definitely stay away from

those that are brass or

aren't nickel plated as the tool is being reproduced by

modern toolmakers. The

originals will have "STANLEY" stamped into the left cheek,

and the

earlier one will have the patent date, "PAT AP'L 10-88"

stamped into

the right cheek.

#97 Cabinet makers' edge plane, 10"L, 2 1/4"W, 3 3/4lbs, 1905-1943. *

This plane sorta looks

like a wedge with a turned rosewood knob at its rear. The

knob, always a low

style, is identical to those used on the evil #6, and it sits atop a raised

ring in the casting to

help reduce the likelihood of its chipping about its base.

The knob is secured

to the plane with the common threaded post and nut, but

the nut is nickel

plated, unlike the nut used on the common bench planes.

This plane sorta looks

like a wedge with a turned rosewood knob at its rear. The

knob, always a low

style, is identical to those used on the evil #6, and it sits atop a raised

ring in the casting to

help reduce the likelihood of its chipping about its base.

The knob is secured

to the plane with the common threaded post and nut, but

the nut is nickel

plated, unlike the nut used on the common bench planes.

There is no mouth on this plane - it has no bearing

surface ahead of the

cutter making the plane really nothing but a chisel held at

a constant pitch

and regulated by the sole to prevent it from digging into

the wood too deeply.

The plane carries a cutter that is as wide as the

plane is with it bedded

bevel side up. The cutter is pitched at about 20 degrees,

and it rests on the

sides of the bottom casting, which are machined to form an

inclined plane. If

you were to use this plane, and forget its value as a

collectible, you'd want

to make sure that the machining was true with both sides in

the same plane. The

entire length of the backside of the cutter does not rest on

the side rails;

only the leading edge of the cutter makes direct contact

with the side rails

and the bed proper.

The cutter is held in place by a thumb

screw-activated lever cap that is

entirely japanned. The cutter is adjusted by the familiar

screw mechanism found

on the common block planes. The sides of the plane each have

a U-shaped cutout

on them to allow better access to the adjusting screw. The

sides are also

machined at right angles to the sole.

The plane was marketed

to piano makers in particular and cabinetmakers in general.

It was designed to

cleanup or trim inside work, where the space is limited and

the use of any

other plane is impossible. Obviously, this a very special

purpose plane for

rare occurences in the shop.

The plane was marketed

to piano makers in particular and cabinetmakers in general.

It was designed to

cleanup or trim inside work, where the space is limited and

the use of any

other plane is impossible. Obviously, this a very special

purpose plane for

rare occurences in the shop.

Like the #62, these planes have a tendency for chipping at the

leading edge of the

bottom casting, directly below the cutter, due to the

thinness of the casting

there. The left and right corners of the leading edge on

some examples of these

planes are not finished at a right angle, but are instead

slightly angled in an

attempt to reduce chipping.

Chipping doesn't harm the plane's use, as long as the

chipping isn't too

severe, but it really kills the plane's value to your

average Stanley collector.

If yours is chipped, and you can't sell it to a collector,

you can always use

it as a doorstop - its wedge-shape makes it perfect for that

role.

Check that the tool hasn't been reworked, where an

example, with a minor

chip, was machined to eliminate the defects. Sight down the

machined side

rails, on which the cutter rests, to make sure they are

straight and true. Any

deviance from a straight edge on these means that a portion

of the side rails

has been machined so that the leading edge can be cut back a

bit to eliminate

the chip. The underside of the cutter clears the back end of

the machined side

rails by about 1/16"; if it's less than that amount, chances

are that the

plane was chipped and remachined. One of the tell-tale signs

of a re-work is the

machining marks at the very end of the casting, where the

chipping occurs;

original machining leaves curved milling marks concentric

with each other a la

the layers of an onion. The marks are very fine, but they

are there.

The earlier castings, down along the U-shaped

'cut-outs' of the side rails,

do not have the quarter-sphere bumps that the later castings

do. These 'bumps'

were likely added to the casting to give it strength and to

make the pattern

pop free of the sand easier during the casting of the tool.

#98 Side rabbet plane, 4"L, 1/2"W, 1/2lb, 1896-1942.

This is a small and

rather flat plane with a narrow cutter secured diagonally

across the plane's

main casting. Behind the cutter is a small, turned, rosewood

knob. The cutter

is secured with a sorta J-shaped clamping mechanism, which

is tightened with a

thumb screw (check that this thumb screw isn't stripped, as

many of them are).

The plane has a very narrow "sole," which is more like the

runners,

or skates, on a #45 than it is a sole (in the bench plane sense). The

backside of the

plane is machined flat.

This is a small and

rather flat plane with a narrow cutter secured diagonally

across the plane's

main casting. Behind the cutter is a small, turned, rosewood

knob. The cutter

is secured with a sorta J-shaped clamping mechanism, which

is tightened with a

thumb screw (check that this thumb screw isn't stripped, as

many of them are).

The plane has a very narrow "sole," which is more like the

runners,

or skates, on a #45 than it is a sole (in the bench plane sense). The

backside of the

plane is machined flat.

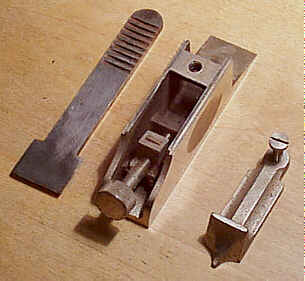

The front portion of the skate is reversible so the

plane can be worked in a

bull nose fashion, as shown in the lower example in the

photograph. This

portion is secured to the main casting with a small

countersunk screw. Make

sure that the bull nose section hasn't been snapped off from

misuse. Curiously,

many of the planes are broken, and repaired on the main

casting where the

portion that carries the knob widens to meet the rest of the

casting. Like the #79, this

plane, and the #99, can suffer cracking to the casting along the

milled bed of the

cutter. See the #79's listing for that

information.

The plane is used to cleanup the sides of rabbets,

dadoes, grooves what have

you. Like the #79, the cutters on this plane are far too narrow for

me, so I, instead,

have a wooden pair, where I can utilize their capability

to make larger cuts.

That, and the fact that these are very small planes which

I find difficult to

grasp comfortably. However, unlike wooden side rabbets,

which tend to have

wider soles than this plane, the #98 & #99 can undercut sides better, like when doing the

housing for a sliding

dovetail. The other knock against wooden side rabbets is

that they can, and

often do, warp over their length. This plane does not

suffer that flaw.

This plane is referred to as the right one of the

pair, which means it is

pushed from left to right with its knob facing your body.

This is kinda weird,

seeing how it is opposite the way a conventional plane is

pushed - from left to

right - when this plane is said to be for righthanded use.

The plane was introduced prior to the #99, its mate, to see how well it

would be received by

the public. Apparently, it went well for the planes aren't

all that rare. The

earliest models have the patent date stamped into the

skate. Starting around

1930, the plane came equipped with an adjustable depth

stop located on the

backside. The depth stop is secured to the plane with a

small thumb screw, and

the backside of the plane has a vertical V-groove cut into

it to accept a

tongue-like surface on the depth stop. This mating of the

depth stop and main

casting is identical to that used on the #78, and similar planes, and helps

to keep the depth

stop laterally stable so the sole of the stop is parallel

to the surface being

worked.

One may wonder why to go with this plane and its

brother over the #79, which

rolls the functions of both planes into a single tool. On

the plus side, the #79 is easily

half the cost of the #98 and #99 combined, as might

be expected since two planes should be twice the cost of

one, right? The best

reason to go with the pair of planes over the #79 is that

you can always leave the irons set in the pair, whereas

you have to back off

the 'trailing' iron of the #79, if you want to follow good

planing practice.

Dragging an iron backward over wood can dull or injure it.

Some folks will take the knob off the plane and use

it on a #1 that's in

need of knob (the #1 is more valuable than the #98, so it's sacrificed for the

cause). The knob is

held to the plane using the common threaded rod and

slotted nut, but the nut on

this plane is nickel plated. The blade clamp is

interchangeable with the #79.

#99 Side rabbet plane, 4"L, 1/2"W, 1/2lb, 1897-1942.

This plane is the left one of the pair - it is pushed from right to left. It is identical to the #98, except that it is the mirror image of that plane. These planes are found less frequently than the #98's are. The plane is the topmost one pictured under the #98's description.

#100 Block plane, 3 1/2"L, 1"W, 3/8lb, 1898-1958.

Never thought I'd make it

to #100, did you?

Well, neither did I.

Sad thing is, I've got another 100, or so, to go. UGH!

What a thankless task

this is. I wish I had listened to my father's advice to

become a professional

wrestler, er, where was I? Oh yeah, this is a toy-sized

block plane, designed

to be used with one hand. It has a squirrel tail iron

handle at its rear, which

rests nicely in the palm of the hand. The handle has a

hole drilled in it so

that the tool can be hung out of the way.

Never thought I'd make it

to #100, did you?

Well, neither did I.

Sad thing is, I've got another 100, or so, to go. UGH!

What a thankless task

this is. I wish I had listened to my father's advice to

become a professional

wrestler, er, where was I? Oh yeah, this is a toy-sized

block plane, designed

to be used with one hand. It has a squirrel tail iron

handle at its rear, which

rests nicely in the palm of the hand. The handle has a

hole drilled in it so

that the tool can be hung out of the way.

The plane is particularly suited for miniature and

model work. A simple

screw-activated lever cap, which is forced against a rod

that extends across

the plane's width (cheek to cheek), is used to secure the

cutter in place. This

same method of securing the cutter is common to other planes

that follow. There

is no cutter adjustment mechanism; this is done entirely by

hand.

Later models, ca. post-WWII, have their lever caps

finished in red paint which

gives them a unique look from the ones that are all

japanned. Many of the

planes have no markings on them, including the cutter.

[ START ] |

[ PREV ] | [ NEXT

] | [ END ]

[ HOME

]

Copyright

(c) 1998-2012 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved.

No part may be

reproduced by any means without the express written

permission of the author.