The Superior Works: Patrick's Blood and Gore Planes #9 - #11 1/2

Quick Find:#9, #9 1/4, #9 1/2, #9 3/4, #10, #10C, #10 1/4, #10 1/4C, #10 1/2, #10 1/2C, #11 (belt), #11 (bull), #11 1/2

#9 Cabinetmaker's block plane, 10"L, (8 1/4" 1936 on), 2"W, 4 1/2lbs, 1870-1943. *

This

plane has no number cast on

it. It is a rectangular, box-shaped plane sold as a high

quality tool designed

for the finer work of piano making and cabinet making. Its

sides are ground

flat and are square with the sole so that the plane can be

used on its side (to

function as a shooting plane and fine endgrain work) either

right or left

handed. The exterior of the tool is bare machined metal

while the inside of the

plane is japanned. The cutter is pitched at about 20 degrees

and is bedded in

the plane bevel side up.

This

plane has no number cast on

it. It is a rectangular, box-shaped plane sold as a high

quality tool designed

for the finer work of piano making and cabinet making. Its

sides are ground

flat and are square with the sole so that the plane can be

used on its side (to

function as a shooting plane and fine endgrain work) either

right or left

handed. The exterior of the tool is bare machined metal

while the inside of the

plane is japanned. The cutter is pitched at about 20 degrees

and is bedded in

the plane bevel side up.

It has a rear knob, made of rosewood, which is

secured onto a metal

extension that is itself screwed into the body of the plane.

Always check where

the body and the extension piece are screwed together for

stress cracks. The

force on the plane, as it's pushed, often breaks the casting

here.

The mouth is adjustable. There is a round-headed

screw on the top of the

tool, toward the throat, to set the mouth as fine as the

user wishes (within

its limits). If this screw is tightened too much, it can

crack the casting. A

washer was added to overcome this problem on later models.

There is a sausage-shaped and nickel plated side

handle, often called the

'hot dog', which attaches with a screw on either side of the

plane. This handle

is often missing, but the earliest model of the plane never

had it. There are

reproduction side handles available. The original handle is

easy to distinguish

from the reproduction - the original is cast and is hollow

inside whereas the

reproduction is milled from round stock and shows machining

marks inside it.

It's a good idea to remove the side handle before purchasing

the plane (unless

it's priced ridiculously low) to inspect the side rail for

any cracks or

missing chunks which the side handle can easily hide.

The lever cap is

specially designed for this plane. It looks like a

conventional bench plane's

lever cap, but its neck (the narrowest part of the cap) is

longer than the

common lever caps used on the bench planes. Unscrupulous

dealers will use a #4 lever cap as a

replacement. Just make sure the pivot point of the lever

rests near the back

wall of the plane's body, where the handle extension

screws into the body. The

latest lever caps will have "STANLEY" cast into them.

The lever cap is

specially designed for this plane. It looks like a

conventional bench plane's

lever cap, but its neck (the narrowest part of the cap) is

longer than the

common lever caps used on the bench planes. Unscrupulous

dealers will use a #4 lever cap as a

replacement. Just make sure the pivot point of the lever

rests near the back

wall of the plane's body, where the handle extension

screws into the body. The

latest lever caps will have "STANLEY" cast into them.

Like all the block planes made by Stanley, the cutter

for this model is

bedded with its bevel up. Since this plane used a

conventional bench plane

cutter, the company logo that's stamped at the heel (top) of

the iron isn't

visible when looking at the plane from above. Stanley would

stamp their logo on

some of the irons destined for this plane with the logo on

the bevel side as

well, making for irons that have the logo on both sides.

This same treatment

can also be found on the planes #11, #11

1/2, and #25.

The cutter has an adjustment mechanism based upon the

same style as that

used on the bench planes - a y-shaped fork engages a slot in

the 'cap iron' and

is adjusted by means of a brass nut. An early model of the

plane (up to the

late 1890's) has its brass nut travel in a direction

perpendicular to the heel

of the plane, whereas the later model has the brass nut

travel perpendicular to

the cutter. There was never a lateral adjustment mechanism

offered on the

plane.

The 'cap iron' on this

tool is really not a cap iron, in the conventional sense,

like those used on

the bench planes. Instead, this 'cap iron' only serves to

engage the y-shaped

fork so that the cutter can take advantage of the patented

adjusting mechanism.

This 'cap iron' is a rectangular shaped piece of steel (the

short ends have a

small convex radius to them), about 1" x 2" in dimension.

The same

'cap iron' is also found on the #11, the #11 1/2, the #25, and the #164.

The 'cap iron' on this

tool is really not a cap iron, in the conventional sense,

like those used on

the bench planes. Instead, this 'cap iron' only serves to

engage the y-shaped

fork so that the cutter can take advantage of the patented

adjusting mechanism.

This 'cap iron' is a rectangular shaped piece of steel (the

short ends have a

small convex radius to them), about 1" x 2" in dimension.

The same

'cap iron' is also found on the #11, the #11 1/2, the #25, and the #164.

There are several very early examples of this tool,

when Leonard Bailey

himself was making them, which have markedly different

adjusting mechanisms

than the models that Stanley produced. The very first model

didn't come

equipped with any rear grip (no rosewood knob). The knob was

soon added,

probably soon after Bailey's complaint department was

flooded with death

threats from unhappy users of this plane - just looking at

it will make your

hands bleed.

This plane is modelled after similar English planes (Spiers-type)

and after the New York City area planemakers (Brandt, Erlandsen,

Popping, et al). While certainly a clever and nicely made

plane, it is a

distant runnerup when compared with those that inspired it.

It attempted to be

too much, when it didn't need to be. The other planes had no

contraptions for

adjusting their cutters - they excelled because they were

simple, well crafted,

and accurate.

#9 1/4 Block plane, 6"L, 1 5/8"W, 1 1/4lbs, 1947-1982.

This is the first in a

series of block planes, which Stanley offered in practically

every shape and

color. Buying a block plane, as we are about to see, was

almost like buying an

automobile, where options galore were available to Mr.

Planebuyer of

yesteryear.

This is the first in a

series of block planes, which Stanley offered in practically

every shape and

color. Buying a block plane, as we are about to see, was

almost like buying an

automobile, where options galore were available to Mr.

Planebuyer of

yesteryear.

Stanley, in their marketing propaganda, claimed that

"A Block Plane

was first made to meet the demand for a Plane which could

be easily held in one

hand while planing across the grain, particularly the ends

of boards, etc. This

latter work many Carpenters call 'Blocking in', hence the

name 'Block' Plane."

This, if it is to be believed, dispells the

myth that block planes are so named because they were

first used on butcher's

blocks.

This is a general purpose block plane (one of many).

It has its iron bedded

at 20 degrees. The iron is adjustable both for depth and

lateral positions. The

mouth is non-adjustable, which is the distinguishing

'feature' that sets it

apart from the more useful #9 1/2. The fixed mouth of this plane

makes it rather

unpopular when pitted against Stanley's other block

planes, most of which have

adjustable mouths. The plane has a brass front knob that

screws into the main

casting - the knob is sometimes missing in action. The

area of the casting into

which the knob threads sometimes chips or cracks, and it

should be checked for

that damage, if you're collecting the thing, but if you're

using it, the damage

isn't severe enough to prevent the plane from working.

As is the case for most of the Stanley block planes,

the earliest models

were japanned (black). Later production planes were finished

with a very dark

blue paint starting in the early 1960's. The latest

production used a very deep

red as a finish. The same progression of paints can also be

found on the bench

planes.

Refer to the #9 1/2 for the details of construction, use, and

problem areas with this

plane, and most of the 20 degree pitch block planes that

Stanley cranked out in

all sorts of configurations.

#9 1/2 Block plane, 6"L, 1 3/4"W (1 5/8"W 1909 on), 1 1/2lbs, 1873-1981.

This

is a general purpose block

plane, and is probably Stanley's most popular one they

offered. Unless this

plane was your great grandpappy's, it's usually best to

ignore those examples

that are all rusted or are missing parts. It's such a common

plane (in its

post-1890's configuration) that you'll run across a better

example.

This

is a general purpose block

plane, and is probably Stanley's most popular one they

offered. Unless this

plane was your great grandpappy's, it's usually best to

ignore those examples

that are all rusted or are missing parts. It's such a common

plane (in its

post-1890's configuration) that you'll run across a better

example.

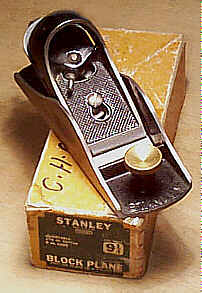

Pictured here, along with Santa Claus, is the typical

configuration of the

plane that you're likely to encounter (details below). The

box, with its faux

birch paper, is known as the Christmas box and was designed

to display the tool

in a hardware store setting during the Holiday Seasons of

the late 1940's and

early 1950's. Santa Claus was not shipped with the plane. An

unemployed

Salvation Army Santa - we found him roaming the streets

dejected - was offered

the opportunity to pose with the tool and graciously

accepted (note: Santa

isn't to scale, here).

The iron is placed into the plane bevel side up. An

iron that's oriented

bevel-up offers advantages when planing difficult woods or

endgrain; it's

possible to support a greater length of the iron, preventing

its flexing, on a

plane designed to carry its iron bevel-up than a plane

designed to carry its

iron bevel-down. The iron is pitched at 20 degrees. The

iron's pitch and

orientation make a cap iron unnecessary, and impractical for

that matter.

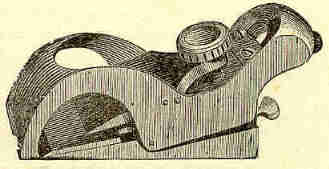

The plane underwent several modifications over its

long life. The first

model is a very primitive looking chunk of iron, with an

iron that extends up

and behind the tool making for a very uncomfortable grip.

This model has a flat

lever cap, with a cammed lever at its top, which resembles

the lever caps used

on the bench planes. The mouth piece is held in place with a

round-headed

screw. The arched sides of the plane's main casting are

curved irregularly and

are situated toward the back. This style of casting is often

referred to as the

'Excelsior' design.

The discomfort of

using

the plane was soon addressed by the redesign of the lever

cap. The new lever

cap has a raised and curved portion cast at its back so that

it fits more

comfortably into the palm. It also has the characteristic

three arches cast

down near the leading edge of the cap along with a dimpled

exterior where the

palm rests. Even this new design was tough to grip since the

iron, with its

angular heel, was in the way. It wasn't until the

late-1800's when the heel of

the iron was replaced with a curved one.

The discomfort of

using

the plane was soon addressed by the redesign of the lever

cap. The new lever

cap has a raised and curved portion cast at its back so that

it fits more

comfortably into the palm. It also has the characteristic

three arches cast

down near the leading edge of the cap along with a dimpled

exterior where the

palm rests. Even this new design was tough to grip since the

iron, with its

angular heel, was in the way. It wasn't until the

late-1800's when the heel of

the iron was replaced with a curved one.

Various redesigns of the lever cap were made to

address its fragility and to

make it more comfortable. One such redesign placed the

cammed lever below the

lever cap so that it sits between the lever cap and iron.

This design suffers

breakage on the lever since it is relatively long in order

for it to be

accessible from below and behind the lever cap. During the

late-1890's, the

lever cap underwent its final modification, where the cammed

lever was made

accessible on top of the lever cap with the lever pointing

toward the toe (the

earliest examples can be found with "PAT'D 10-12-97" cast in

a circle

where the lever is pinned to the lever cap). This new design

allowed the length

of the lever to be reduced, thereby decreasing the

possibility of its breaking.

It also permitted the lever cap to be as long as the cutter,

eliminating its

arching upward, making for a more comfortable grip. It took

Stanley a while to

get to this point, but once they did, they stuck with it.

The model most often

encountered is the one offered from ca. 1895 onward. It is

distinguishable by

the oval depressions milled into the exterior of the arched

sides. These are

known as the "Hand-y" grip. The arched sides on most

examples are

symmetrical and are situated along the middle of the sides,

but there are some

examples of the Excelsior design that have the Hand-y grip.

The Hand-y grip feature

soon proved very popular, and was applied to practically

every block plane in

Stanley's arsenal. The feature was dropped for a short time

during WWII,

possibly because Stanley was using the machinery to mill the

same grip on

Howitzer shells so GI's wouldn't drop them on their feet.

The Hand-y grip was

also offered on a few of the shorter, handle-less

transitional (wood bottom)

planes, which are very rarely encountered.

The model most often

encountered is the one offered from ca. 1895 onward. It is

distinguishable by

the oval depressions milled into the exterior of the arched

sides. These are

known as the "Hand-y" grip. The arched sides on most

examples are

symmetrical and are situated along the middle of the sides,

but there are some

examples of the Excelsior design that have the Hand-y grip.

The Hand-y grip feature

soon proved very popular, and was applied to practically

every block plane in

Stanley's arsenal. The feature was dropped for a short time

during WWII,

possibly because Stanley was using the machinery to mill the

same grip on

Howitzer shells so GI's wouldn't drop them on their feet.

The Hand-y grip was

also offered on a few of the shorter, handle-less

transitional (wood bottom)

planes, which are very rarely encountered.

Prior to the patent for the lateral adjustment

mechanism, as specified for

the common bench planes, these block planes only permitted

the iron to be

adjusted endwise to regulate the depth of cut. The earliest

mechanism is a

lever, located beneath the iron, which engages stopped

parallel grooves milled

into the back of the iron via a vertical pin. Moving the

lever laterally

side-to-side, raises or lowers the iron. It also puts a lot

of stress on the

pin, which can snap it off or wear it away. Plus, the lever

also has a pin on

its bottom to slip into a hole in the boss that carries it.

Because it's not

permanently attached to the plane, it's possible to find

planes with this lever

missing in action.

This mechanism proved

to

be rather fragile and was difficult to access so Stanley

redesigned it. The

solution that they came upon is a threaded post adjustment

mechanism and

started offering it during the early 1880's. This post is

screwed into a raised

boss in the main casting. On the post a brass nut traverses

up and down, parallel

to the sole, as the nut is turned. The nut engages a forked

lever, which in

turn engages the grooves in the back of the cutter. As the

nut is turned to

move it upward, the lever lowers the cutter to increase its

set. Moving the nut

downward, naturally, decreases the set. Make sure that this

nut moves freely

over the entire length of the threaded post.

This mechanism proved

to

be rather fragile and was difficult to access so Stanley

redesigned it. The

solution that they came upon is a threaded post adjustment

mechanism and

started offering it during the early 1880's. This post is

screwed into a raised

boss in the main casting. On the post a brass nut traverses

up and down, parallel

to the sole, as the nut is turned. The nut engages a forked

lever, which in

turn engages the grooves in the back of the cutter. As the

nut is turned to

move it upward, the lever lowers the cutter to increase its

set. Moving the nut

downward, naturally, decreases the set. Make sure that this

nut moves freely

over the entire length of the threaded post.

Stanley decided to have some fun with these adjusting

nuts, as some are a

right hand thread while others are a left hand thread.

Almost all of the planes

with the Hand-y grip have the left hand thread. All the

Excelsior style planes

have a right hand thread. This tidbit of information is only

important if

you're looking for replacement parts for the adjusting

mechanism, or if you're

looking for the locking nut used on the #9 3/4 and #15

1/2.

You want to be sure that the two nibs on the fork,

where they engage the

parallel machined grooves cut into the backside of the

cutter, are not broken

or worn away. Otherwise, the adjustment mechanism is

useless. Also, check about

the boss that receives the threaded post for any breakage.

Sometimes, the post

loosens over time; usually, just by wiggling the post you

can tell whether it

is seated into the boss well. It can be tightened by

screwing it back into the

boss, but take care not to damage its threads.

The lateral adjustment lever that was a raging

success on the bench planes

was a feature that the block planes could also use. It took

Stanley a bit of time

to add the lever, but they eventually did during the early

1890's.

The lateral adjustment lever pivots on the lever cap

screw, onto which the

lever cap engages. In fact, the lever screws onto the lever

cap screw, which is

itself screwed into a boss in the main casting. The lateral

adjustment lever

has a disk at its end nearest the mouth, and it fits into a

slot cut into the

iron. It very much resembles the business end of the lateral

adjustment lever

found on the common bench planes. The back of the lever is

bent downward, in a

gradual curvature toward the sole so that it doesn't dig

into your hand during

use. Sometimes, the lateral adjustment lever has been bent

so that it can't

clear the threaded post. If this is the case, you can simply

bend the lateral

lever about its downward curve up a bit so that sufficient

clearance results.

The lateral adjustment lever often has its patent date

and/or

"STANLEY" stamped into it.

The earliest planes

have

an adjustable mouth that uses a slotted screw - you'll need

a screwdriver to

adjust it, if you dare to use this most valuable model of

the tool. This clumsy

adjustment method certainly must have flooded the complaint

department at

Stanley, so the mouth was made adjustable by means of a

brass knob (the

presence of nickel plating signifies that it's a different

model). The knob is

threaded to the sliding section, and by unscrewing the knob

the sliding section

can be moved forward or backward. The knob is then tightened

to lock the

sliding section in place. You should check the threads of

the knob to make sure

they aren't stripped for if they are, your sliding section

will slip out of

your sole and possibly into oblivion.

The earliest planes

have

an adjustable mouth that uses a slotted screw - you'll need

a screwdriver to

adjust it, if you dare to use this most valuable model of

the tool. This clumsy

adjustment method certainly must have flooded the complaint

department at

Stanley, so the mouth was made adjustable by means of a

brass knob (the

presence of nickel plating signifies that it's a different

model). The knob is

threaded to the sliding section, and by unscrewing the knob

the sliding section

can be moved forward or backward. The knob is then tightened

to lock the

sliding section in place. You should check the threads of

the knob to make sure

they aren't stripped for if they are, your sliding section

will slip out of

your sole and possibly into oblivion.

During the late-1890's, an eccentric lever was

provided to adjust the mouth

(the earliest examples will have the patent date, "PAT FEB

20 94",

stamped in them). This little device soon was applied to

every block plane that

was equipped with an adjustable mouth. It's really a simple

little device - a

flat piece of steel, with an extension for your finger,

pivots on a pin which

fits into a hole behind the knob. This piece is not held

captive to the plane,

and it's very easy to lose. If you see a small hole

immediately behind the

knob, your plane is missing its eccentric lever. Also be

sure to check the eccentric

lever to see if it has its post that fits into the casting.

Strangely, many of

the levers are still on the planes but don't have the post.

You should check that the eccentric lever is proper

for the plane by sliding

it to the left and right, making sure that the sliding

section of the sole

moves within the acceptable range. Because this lever was

often removed from

the plane (the owner simply found it easier to adjust the

sole without it), and

because the same lever was offered on the smaller block

planes, it's sometimes

possible to find planes with an improper lever - a lever

from the smaller #60 1/2 will not

permit the sole to be adjusted over as wide a range as a

proper one will.

The sliding section of

the sole is oftentimes jammed into the plane so that it no

longer moves freely.

The usual cause of this is that either oxidation has frozen

it in place or that

crud has become lodged between it and the main casting. To

overcome this common

problem you first need to free the sliding section from the

main casting. This

is easily done by first backing off the knob that holds it

in place with a few

turns, then pushing the knob downward with your thumb. The

piece should pop

free, but if it doesn't, take more drastic measures like

penetrating oil or

light taps from a hammer. Save the dynamite as last resort.

I've never found

one that ultimately didn't come free with a piece of wood

(stood on its

endgrain) positioned in the mouth (from the top of the

plane) and then tapped

with a hammer.

The sliding section of

the sole is oftentimes jammed into the plane so that it no

longer moves freely.

The usual cause of this is that either oxidation has frozen

it in place or that

crud has become lodged between it and the main casting. To

overcome this common

problem you first need to free the sliding section from the

main casting. This

is easily done by first backing off the knob that holds it

in place with a few

turns, then pushing the knob downward with your thumb. The

piece should pop

free, but if it doesn't, take more drastic measures like

penetrating oil or

light taps from a hammer. Save the dynamite as last resort.

I've never found

one that ultimately didn't come free with a piece of wood

(stood on its

endgrain) positioned in the mouth (from the top of the

plane) and then tapped

with a hammer.

Once free, clean out any of the crud that's

accumulated over the years.

Check that the boss cast into the sliding section, which

receives the knob,

isn't broken. Curiously, many of them are.

If the sliding section doesn't move freely, you can

do a bit of plane

surgery to remedy the ailment. With some fine abrasive paper

on a flat surface,

rub the edges of the sliding section back and forth a few

times to remove any

oxidation or burrs. Take the same paper and rub the milled

tracks of the main

casting. Don't overdo it since you will introduce some slop

in what's usually a

fine fit. Reattach the part to the main casting and it will

slide freely.

Make sure that the

sliding section hasn't been modified, where the portion

that's closest to the

iron isn't ground. For some strange reason, some of these

block planes can be

found with their sliding sections ground shorter than when

they left the

factory. Planes with modified sliding sections will not be

capable of having

their mouths set finely. The sliding section should nearly

touch the iron when

the section is moved backward to close the mouth. If it

doesn't, the piece has

been ground. If you do have an example with a ground sliding

section, and are

planning to locate a replacement part, take care when doing

so; the replacement

section my be too thick or thin, and not lie in the same

plane as the rest of

the sole. I've yet to find a block plane that can accept a

sliding section

taken from another block plane without some modification.

Make sure that the

sliding section hasn't been modified, where the portion

that's closest to the

iron isn't ground. For some strange reason, some of these

block planes can be

found with their sliding sections ground shorter than when

they left the

factory. Planes with modified sliding sections will not be

capable of having

their mouths set finely. The sliding section should nearly

touch the iron when

the section is moved backward to close the mouth. If it

doesn't, the piece has

been ground. If you do have an example with a ground sliding

section, and are

planning to locate a replacement part, take care when doing

so; the replacement

section my be too thick or thin, and not lie in the same

plane as the rest of

the sole. I've yet to find a block plane that can accept a

sliding section

taken from another block plane without some modification.

By far the most common damage found on the plane, as

well as on all models

of block planes, is stress cracks that run from the mouth

and up the side(s) of

the tool. These cracks are most often found on the earlier,

pre-1890's, models

since their sides are not cast to a uniform thickness; they

taper along their

edge just like the earlier bench planes do. This was a very

common area for the

plane to break so Stanley made the later models with their

sides cast to a

uniform thickness. Often, these stress cracks are invisible

under the

oxidation. It's only when you give them a cleaning that you

notice the damage.

Don't sweat it if yours is broken here - you're not the

first, nor will you be

the last, to buy such damaged goods.

Another common form of damage is cracks or breaks to

the lever cap, in the

area where it arches to fit into your palm. Cracks here are

really no big deal,

but missing chunks might yield bloody palms. Fortunately,

there are plenty of

lever caps that can be salvaged from the googleplex of block

planes out there.

The planes have a japanned finish, with the brass

knob and depth adjusting

nut all buffed to shine. The lateral adjustment lever and

eccentric lever are

often nickeled, but later ones are just stamped from steel

and buffed. The

plane commonly has its model number stamped into the left

side of the main

casting, down toward the sole. None of the Stanley block

planes came with

corrugations milled into the sole. A few of the mid-1920's

planes can be found

with the day-glo orange paint on the eccentric adjuster and

inside the front

knob. This had to be a phase that Stanley was going through

as some of the

contemporary bench planes have the sides of their frogs

finished with the same

color paint.

#9 3/4 Block plane, 6"L, 1 3/4"W (1 5/8"W 1909 on), 1 5/8lbs, 1873-1934. *

This

plane is identical to the #9 1/2, except that it

has a detachable rear handle. The handle is a metal

extension that fits around

and is fixed to the same threaded vertical post that the

depth adjustment nut

is. A locking nut is screwed onto the post and then is

tightend over two metal

prongs on the handle. The handle can be removed to suit

the workman's use

simply by backing off the locking nut with the end of a

screwdriver. The

locking nut has four "lobes" on it making it resemble an

"x".

This

plane is identical to the #9 1/2, except that it

has a detachable rear handle. The handle is a metal

extension that fits around

and is fixed to the same threaded vertical post that the

depth adjustment nut

is. A locking nut is screwed onto the post and then is

tightend over two metal

prongs on the handle. The handle can be removed to suit

the workman's use

simply by backing off the locking nut with the end of a

screwdriver. The

locking nut has four "lobes" on it making it resemble an

"x".

Because Stanley was never satisfied to leave well

enough alone, they changed

the width of the boss onto which the pivotting lever (the

one that engages the

underside of the cutter) fastens. This subtle design change

meant a similar

change in the detachable handle; the distance between the

two prongs had to be

increased just a hair so that the prongs can slip around the

boss. This minor

point is only mentioned in the event that you have a handle

and you're trying

to fit it to a plane. Do not ever force the handle or file

it if it doesn't fit

- you have an earlier two prong handle that needs to go on

an earlier version

of the plane.

The metal extension

has

a turned rosewood knob that fits into the palm of the hand,

allowing the plane

to be worked more comfortably with both hands. The earliest

versions of the

plane use the common threaded rod and brass nut to secure

the rosewood knob to

the the extension piece. On later models, the rosewood knob

is tapped and

screws directly onto the threads cast into the metal

extension. On these later

models, the knob can strip and become loose over time. The

usual quick fix was

to jam a shaving or a piece of cloth into the knob and then

allow friction to

work its magic.

The metal extension

has

a turned rosewood knob that fits into the palm of the hand,

allowing the plane

to be worked more comfortably with both hands. The earliest

versions of the

plane use the common threaded rod and brass nut to secure

the rosewood knob to

the the extension piece. On later models, the rosewood knob

is tapped and

screws directly onto the threads cast into the metal

extension. On these later

models, the knob can strip and become loose over time. The

usual quick fix was

to jam a shaving or a piece of cloth into the knob and then

allow friction to

work its magic.

Prior to the introduction of the threaded vertical

post, the metal extension

piece was screwed right to the main casting, beneath the

iron. This model is

comparatively scarce, and was only made for a few short

years. It can be

identified easily by a screw hole at its end and an open

casting that gives the

appearance of two ribs projecting from the knob. This style

of handle was used

only on the two earliest models of the plane, from 1872 to

about 1875. Check

these handles carefully for cracks over their length.

Most of the metal extensions are japanned, but the

very earliest ones have a

copper flashing to them, which is usually long gone and hard

to find today. Be

careful that the knob is proper, and not one lifted from a

#45. The #45's knob

(referring to the model that threads the knob onto the

fence's casting in the

same manner as it is on the block plane's extension handle)

is a hair small in

its diameter and doesn't have the ring turned at its base.

#10 Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 14"L (13"L 1887 on), 2 1/8"W, 4 1/4lbs, 1870-1957.

This plane is sometimes

called the 'jack rabbet' due to its similarity to the common

jack plane. It

looks identical to a conventional #5, except that it has a rabbet

mouth. The rabbet

mouth is two cutouts in the plane's sides, just to the

left and right of the

iron. The iron extends through these cutouts and across

the entire width of the

sole. These planes have always been popular, with their

full adjustment

features identical to those found on the bench planes.

This plane is sometimes

called the 'jack rabbet' due to its similarity to the common

jack plane. It

looks identical to a conventional #5, except that it has a rabbet

mouth. The rabbet

mouth is two cutouts in the plane's sides, just to the

left and right of the

iron. The iron extends through these cutouts and across

the entire width of the

sole. These planes have always been popular, with their

full adjustment

features identical to those found on the bench planes.

They were used for cutting large rabbets in heavy

timbers for framing in the

mining, carriagemaking, etc., professions. Since the plane

has a rabbet mouth,

and because it was designed for heavy use, many of them have

stress fractures

in the casting right above the rabbet mouth, where the sides

arch upward. Many

of them have been repaired with a welding, which sticks out

like a sore thumb,

usually, but some repairs are very good and can go

undetected. The planes also

seem to suffer chipping/cracking along their side walls,

especially about the

toe and heel. The earlier models, with their tapered side

walls, are more prone

to this chipping/cracking than the later ones are.

Another thing to check on these planes is their

irons. Because of the rabbet

mouth, there isn't nearly enough space to make an iron that

is as long as those

found on the conventional bench planes - the sides of the

plane prevent it from

being as long as the others. Be sure to check that there is

enough 'meat' or

life left to the iron. Finding replacements that are proper

to the vintage of

your plane can be tough. Also, the cap iron should cover the

full width of the

iron along the cutting edge. If it doesn't, it's a

replacement from a normal

bench planes.

Removing the irons from this plane, and the #10 1/2, is a bit of a trick. They

cannot be removed

through the mouth, and they are prevented from being

removed as you normally

would an iron by the sides of the plane. To remove the

iron, then, you must

first tip it up so that it clears the lever cap screw,

then slide it to either

side of the plane, and then lift the opposite side up,

sort of in a twisting

fashion, until one side of the iron clears the cutout in

the side of the plane.

Stanley recognized the problem with removing or

returning the iron from or to

the plane. Returning the iron to the plane needs a bit of

attention so that you

don't nick the edge, ruining the honing effort that took you

hours to get. To

overcome this problem, Stanley redesigned the cap iron and

the way it was

attached to the iron. A small screw was positioned on top of

the cap iron so

that once removed, the iron would slip through the mouth

easily. Problem

solved, or so Stanley thought. This short-lived (ca. late

1880's) feature

proved to be a problem when reassembling the iron - trying

to position the cap

iron properly on the iron, while both are in the plane

proved to be awkward and

difficult. They soon dropped the design for the normal

method of attaching the

cap iron (the screw is behind the iron and is only

accessible with the iron

removed from the plane).

These planes, along with the fractional versions of

it, never came equipped

with the frog adjusting screw that's found on the bench

planes. In fact, all

the frog redesigns made to the bench planes never made it to

this line; the

bench rabbets retain their flat mating surfaces between the

frog and the main

casting. However, the planes did follow the changes made to

the lever cap, the

adjusting screw, the knob, and the tote that were done to

the bench planes (see

their type study for more features).

As is the case with all rabbet planes, a batten is

normally fastened to the

work at the desired with of the rabbet. The batten then

guides the plane along

its path to yield a straight cut. The depth of the rabbet is

normally marked with

a common marking gauge. For cross grain work, the rabbet's

shoulder is usually

cut with a saw prior to using the plane since this plane

doesn't come equipped

with a spur to score the grain.

If you ever need a lever cap for this plane, or the

other bench rabbets that

follow, the #3's will work. The old style #3 frog also fits the

plane; i.e., the frog that

doesn't have a notch (to fit over the alignment rib in the

main casting) milled

at its lower edge.

#10C Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 14"L, 2 1/8"W, 4 1/4lbs, 1902-1918. *

The corrugated version of the #10. A brute of a dude, who had taken to planing rabbets in heavy timbers as a career, certainly didn't need any 'girlie-man' corrugations in the sole to make his job any easier. This may be one of the reasons for the scarcity of the corrugated model of this plane.

#10 1/4 Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 13"L, 2 1/8"W, 4 1/4lbs, 1911-1942. *

This plane is identical to the #10, except that it has a tilting tote and knob. This idea was first patented by a guy who added tilting wood to regular #10's because he found that your knuckles got all smashed when planing large rabbets. Stanley, being the nice guys they were to their competition, decided they could do it themselves, and made their own version of it thereby making the originator of the idea a footnote in the history of planes.

The tote and knob each sit atop a rounded casting

that holds a coarsely

knurled metallic cylinder. The usual securing rods for the

tote and knob are

screwed into these knurled cylinders. At the top of each

securing rod is a

slotted nut, which is tightened to secure the tote and knob

in a slanted

position, tilted from the vertical, that the user finds

comfortable. The

slotted nuts are often mangled from repeated use.

Often the wooden parts, especially the lower portion

of the tote, are found

cracked or broken off around their bases from years of use.

The wooden parts

are custom made for this plane, so trying to salvage a tote

or a knob from a

standard jack plane is pointless; original totes and knobs

have a concave bottom

so that they can fit over their respective convex portions

of the main casting.

The same problem of stress fractures about the sides

of the bottom casting,

as found on the #10,

also happens with these planes.

Two retractable spurs, one on each side of the plane,

are used to score the

wood before the iron cuts it. These spurs help to eliminate

ratty edges on the

rabbet, especially when working across the grain. The spurs

are attached to the

plane with small countersunk screws. The screws often show

signs of mangling

from repeated use. The earliest models of this plane do not

have these spurs.

It's interesting that Stanley only offered these spurs on

this plane, and not

the other bench rabbet planes. Perhaps they realized that

they made a mistake

by offering this tool and to save face they added the spur

feature to boost

sales by making them really different from the #10 and #10 1/2. Sounds good to me, at least.

In any event, the

spurs certainly assist the plane when cutting across the

grain, making for a

clean shoulder.

I've seen a WWII model of this plane, where hard

rubber, instead of brass,

was used for the cutter's depth adjustment knob and the tote

and knob are hardwood

instead of rosewood. There is no nickel plating on the lever

cap. With this

plane's sales being rather anemic from its introduction, it

seems strange that

Stanley would even make a Warlwartwotype (pronounced

properly as a single

syllable). Planing large timbers during WWII certainly had

to be a lost 'art'

in the States, but maybe not so in the Orient. Perhaps

Stanley kept up the

production of the plane in anticipation of the building of a

bridge over the

river Kwai, or something?

#10 1/4C Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 13"L, 2 1/8"W, 4 1/4lbs, 1912-1917. *

Corrugated version of the #10 1/4. Putting corrugations on a plane, which probably was better left on the drawing board in the first place, makes for a very rare plane. This is a tough one to find, one of the toughest of all Stanley planes, so be careful of the modern artisan's craftiness.

#10 1/2 Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 9"L, 2 1/8"W, 3lbs, 1885-1964.

This

is sometimes called the

'smooth rabbet' since it is the same size as a #4, however in some of Stanley's

earlier propaganda

this plane and the #10 are both simply called a

"Carriage Maker's

Rabbet". The usual problems with the #10, and the other bench planes,

are also found on this

guy. The most common form of damage are cracks and/or

repairs to the cheeks of

the tool, located just above the cutouts for the cutter.

This

is sometimes called the

'smooth rabbet' since it is the same size as a #4, however in some of Stanley's

earlier propaganda

this plane and the #10 are both simply called a

"Carriage Maker's

Rabbet". The usual problems with the #10, and the other bench planes,

are also found on this

guy. The most common form of damage are cracks and/or

repairs to the cheeks of

the tool, located just above the cutouts for the cutter.

The earliest models have an adjustable mouth, very

much like those found on

the common block planes, but the entire section of the sole

ahead of the iron

moves. Adjustable mouth versions are much scarcer than the

non-adjustable mouth

versions, and were only offered for about the first ten

years of the plane's

production.

The mouth is adjusted by turning the front knob,

sliding the knob forward or

backward, and then tightening the knob; this action moves

the entire sole ahead

of the iron. The casting that receives the front knob's

screw is sometimes

broken so take the plane apart to inspect this. The

repetitive adjustment to

the mouth also puts wear and tear on the rosewood knob; many

of them are split

or are chipped at their bases. I've seen some of these early

models with a

metallic disk under the knob in an attempt to overcome the

chipping that the

knobs suffer; this disk appears original and is similar to

the one used on the #62.

This plane always came with the lateral adjustment

lever - if you see one

that doesn't have one, it's likely from an earlier #3 or #10.

#10 1/2C Carriage maker's rabbet plane, 9"L, 2 1/8"W, 3lbs, 1902-1917. *

Corrugated version of the #10 1/2. It never came with an adjustable mouth, to the best of my knowledge. Because this plane is much more valuable than its non-corrugated brother, be careful of counterfeit corrugations.

#11 Beltmaker's plane, 5 3/4"L, 2 3/8"W, 3 1/2lbs, 1867-1943.

Hey,

if you're into making, or

repairing, the belting used for driving machinery, get with

it, will ya? We're

about to enter a new century never mind a millenium, too!

But for those of you who

want the frightening details, read on....

Hey,

if you're into making, or

repairing, the belting used for driving machinery, get with

it, will ya? We're

about to enter a new century never mind a millenium, too!

But for those of you who

want the frightening details, read on....

The cutter is positioned bevel side up, and is bedded

~25 degrees. There is

no cap iron proper on the plane, but it does have a small

cap screwed to the

top of the cutter, like the #9, #25, and #164 do, so that the tool can take

advantage of the

Bailey adjustment features like those found on the common

bench planes. The

y-shaped adjusting fork engages a slot in the small cap.

This slot is oriented

toward the heel, not the cutting edge, of the iron.

It seems that those who practiced the beltmaking

trade were a trifle bit

spastic - many of these planes have broken adjusting forks.

This problem

resulted from insufficient pressure, via the lever cap,

being placed on the

iron, when it had a rank set. When the iron started its cut,

it immediately

jumped backward which then strained the adjusting fork where

it makes contact

with the brass depth adjustment knob, causing it to snap. If

you plan to

resurrect the beltmaking trade, and your plane has a broken

adjusting fork, you

will have to replace it with a fork from another #11 (or #11 1/2) - the adjusting forks from

the bench planes are

not interchangeable with this model.

Sometimes, insufficient pressure on the iron will

cause the back part of the

casting to snap off or crack, where the threaded rod fits

into the casting.

Broken chunks off the casting are easy to spot, but to see

the stress cracks

takes a keener eye. Look closely about the rear of the

plane. Take the iron out

of the plane and look (from the inside of the casting) where

the rod meets the

casting to see if any stress cracks have developed.

The plane looks very similar to the #12, and has a turned hardwood

(most often maple)

handle that is perpendicular and parallel to the plane's

sole. The handle is

screwed to the plane's main casting with two round-headed

srews, each of which

screws into a cast boss. Check that these bosses are not

chipped or cracked.

The cutter is secured in place by a lever cap that is

identical to those

used on the transitional wooden bench planes (see their

listing for a

description). The entire main casting, except its sole and

the machined bed,

are japanned.

The mouth is

adjustable

to satisfy the beltmaker's craving for tearout free planing,

something that's

mandatory when planing leather or fabric belting. NOT! A

small casting

functions as the sliding section found on the common block

planes. It's secured

to the main casting with two round-headed screws, which when

loosened, allow

the sliding section to be moved forward or backward manually

as the village

beltsmithy so desires.

The mouth is

adjustable

to satisfy the beltmaker's craving for tearout free planing,

something that's

mandatory when planing leather or fabric belting. NOT! A

small casting

functions as the sliding section found on the common block

planes. It's secured

to the main casting with two round-headed screws, which when

loosened, allow

the sliding section to be moved forward or backward manually

as the village

beltsmithy so desires.

Oh yeah, why a belt plane? Simple, back before

'lectricity and infernal

combustible engines, water wheels and steam engines supplied

the power to drive

Industrial America (and other joints). Leather and/or fabric

belts were used to

drive the smaller machines off the power source. These belts

have their ends

fastened to each other to form a loop, and it's at the

juncture of the two ends

that a chamfer is cut so that when the ends are fastened

they maintain the same

thickness as the rest of the belt. You had to ask.

This plane was originally offered by Leonard Bailey

prior to his selling out

to The Man, Stanley. His first design is extremely rare. He

eventually made the

plane with a separate frog that is secured onto the main

casting with two

round-headed screws. The threaded rod, on which the brass

depth adjusting screw

rides, is oriented nearly vertically. This construction

proved costly to

manufacture, and the planes were prone to damage, especially

cracks or breaks

where the screws are, so the separate frog idea was dropped

around 1905. The

tool was redesigned with the threaded rod fastened directly

to the main casting

so that it's oriented horizontally. The earliest models of

this tool have a

fair concave curvature to their side walls from the toe of

the plane to the

handle. The later models have a sort of contorted S-shaped

curvature to the

side walls.

#11 Bull Nose Rabbet Plane, 4"L, 1 1/4"W, ca 1880. *

This

is really a strange little plane, in several ways. First, it

wasn't offered in

any Stanley catalog, and judging by where the very few

specimens have turned

up, in England, the plane wasn't sold here in USofA. Second,

this plane's

number designation is identical to the beltmaker's plane,

making these two the

only planes offered concurrently with the same model number.

Why Stanley chose

to designate them the same is anyone's guess, and it's

certainly odd given

Stanley's passion for freely assigning numbers, which the

last time I checked

are infinite, to their manufactured wares. The plane is one

of the very rarest

of Stanley's planes, with only a handful of extant examples.

When other folks

are classifying #340's,

#64's as very rare,

and #3C's

as very scarce, you can ask them how they'd classify this

little bugger then.

This

is really a strange little plane, in several ways. First, it

wasn't offered in

any Stanley catalog, and judging by where the very few

specimens have turned

up, in England, the plane wasn't sold here in USofA. Second,

this plane's

number designation is identical to the beltmaker's plane,

making these two the

only planes offered concurrently with the same model number.

Why Stanley chose

to designate them the same is anyone's guess, and it's

certainly odd given

Stanley's passion for freely assigning numbers, which the

last time I checked

are infinite, to their manufactured wares. The plane is one

of the very rarest

of Stanley's planes, with only a handful of extant examples.

When other folks

are classifying #340's,

#64's as very rare,

and #3C's

as very scarce, you can ask them how they'd classify this

little bugger then.

The plane has a lever adjustment mechanism, identical

to that used on the

common #103 block

plane; a series of

parallel grooves is milled into an adjusting plate, which,

in turn, engage

milled slots cut in the backside of the blade. A thumb

screw pivots the lever

cap to hold the blade in position.

The final strange thing about this plane is that the

small portion of sole,

directly ahead of the blade, can be raised or lowered via

two small set screws

which sit behind the lever cap's thumb screw. This portion

of the sole is

adjusted to work harmoniously with the set of the blade;

i.e., if the blade is

set rank (deeply), the sole is raised, and if the blade is

set fine, the sole

is lowered. This function lends assistance to the plane's

cutting action, for

if the sole were at a constant position, only a minute

portion of it would bear

upon the wood during the planing; the deeper the blade's

set, the less amount

of sole will make contact with the wood. Because the sole

ahead of the iron can

be adjusted, it's practical to make the entire length of

that sole make contact

with the wood prior to the blade's cutting, reducing tearout

and splintering.

It's a geometry thing, here.

The plane was eventually dropped when the #90 cabinetmaker's bull nose rabbet plane

appeared. No sense having two

planes serve the same function, or so one would think.

But, Stanley didn't

adopt this "modus operandi" for too long as they

ultimately produced

concurrently several planes which served the same

function.

#11 1/2 Floor plane, 7"L, 2 3/8"W, 3 3/4lbs, 1909-1923. *

This plane is identical

to the #11, except

that it has an extension piece added to the plane's sole.

This piece is nothing

but the same piece as that on the #11, except it's made longer to

increase the length of

the plane's sole. This piece is secured to the main

casting with two round head

screws. It's possible to regulate the mouth by moving the

piece forward or

backward, relative to the iron.

This plane is identical

to the #11, except

that it has an extension piece added to the plane's sole.

This piece is nothing

but the same piece as that on the #11, except it's made longer to

increase the length of

the plane's sole. This piece is secured to the main

casting with two round head

screws. It's possible to regulate the mouth by moving the

piece forward or

backward, relative to the iron.

The plane has "No. 11 1/2" embossed on the extension

piece,

withing the familiar Stanley notched rectangle. The #11's main casting was used for

this plane. The #11 has its number cast

at its toe. For the #11 1/2, the

#11 casting

number is ground off and then filled with a glob of

japanning. Don't ever buy

an example that has "No. 11" cast into the main casting

and "No.

#11 1/2" cast into the extension piece - it's a monkey,

made up from two

different planes. Also, check the japanning very carefully

where the #11 is ground off. It's

very easy for a crafty 'artist' to practice plane forgery

on these planes where

the plane is converted long after it left the factory.

The iron is normally stamped with the Stanley

trademark on both sides; the

plane beds the iron bevel up, and with the normal iron the

logo would be face

down, thus the reason for stamping the logo on the beveled

side of the iron.

Stanley wanted make it certain that the members of the

floorplaners' union knew

exactly who was using their product.

Be sure to inspect the adjusting mechanism of this

tool as floorplaning was

a rugged task. A snapped adjusting yoke, cracks at the back

of the main

casting, and missing chunks of the main casting are the

major problems with the

tool.

The plane was used in the kneeling position (kneeling

before a false God?)

and is pulled toward you. Ask yourself this question - you

really want one of

these to use? Instead, floor sandahs (sander, in New

England-ese) are so much

more stimulating. Leave this one for the diehard Stanley

junkies as it's a much

scarcer plane than one might think.

[ START ] |

[ PREV ] | [ NEXT

] | [ END ]

[ HOME

]

Copyright

(c) 1998-2012 by Patrick A. Leach. All Rights Reserved.

No part may be

reproduced by any means without the express written

permission of the author.